National film awards: Once upon a time…

Ravi Shanker Kapoor | May 4, 2016 11:26 am

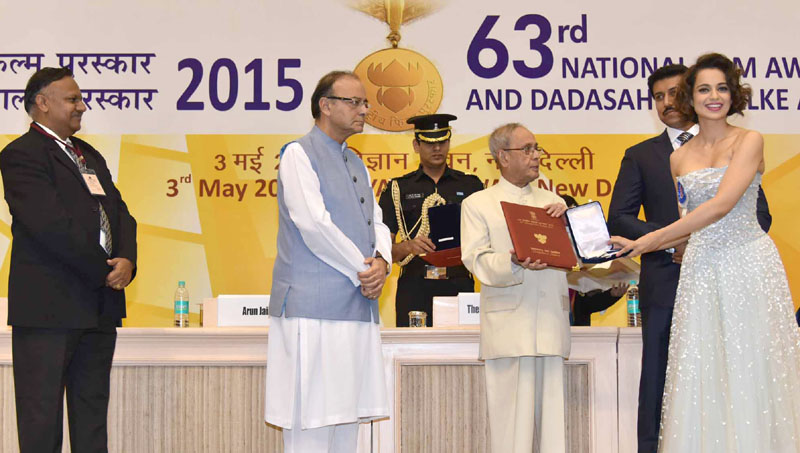

The President, Shri Pranab Mukherjee presenting the Rajat Kamal Award to the Actress Ms. Kangana Ranaut (Best Actress) for Tanu Weds Manu, at the 63rd National Film Awards Function, in New Delhi on May 03, 2016. The Union Minister for Finance, Corporate Affairs and Information & Broadcasting, Shri Arun Jaitley, the Minister of State for Information & Broadcasting, Col. Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore and the Secretary, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Shri Ajay Mittal are also seen.

It is not the first time that national film awards have been accused of being tilted in favor of ‘commercial cinema.’ With movies like Baahubali, Piku, Tanu Weds Manu Returns, and Bajirao Mastani picking up most of the major awards, the old issue did rear its head, but just that. The important thing to note here is that the intensity—which earlier bordered on virulence—of accusations is clearly waning. And this is a good development.

This is not to say that a golden age of Indian cinema has dawned, that the movies awarded the 63rd National Film Awards are great. I have watched Baahubali, Tanu Weds Manu Returns, and Bajirao Mastani; nobody would ever call these as specimens of great art. In fact, I find the very subject of Bajirao Mastani—for which Sanjay Leela Bhansali got the Best Director award—revolting. How could somebody glorify a misogynistic practice, bigamy, in this day and age? How could somebody weave a love story with the warp and woof of multiple wives? The only place for ménage de trios is… well, pornography. But my liking, or lack of it, is beside the point; the striking feature in this context is the diminishing, almost lost, influence of the highbrow Leftwing film critic.

Once upon a time, not very long ago, commerce was commerce and art was art, and never the twain met. The ‘commercial cinema,’ we were lectured by the Keepers of Good Taste, provided garish, kitschy entertainment to the masses, while its arty cousin regaled the men and women of heightened consciousness with ennobling stuff that underlined class struggle, highlighted the pathos of subalterns, prepared the ground for progressive change, exposed the incongruities of ‘false consciousness,’ and galvanized the Enlightened for revolutionary change (It is another matter that Art movies, being dreadfully dreary and boring, were invariably rejected by the masses for whose uplift they were made in the first place, but that’s another story). Since the Left was right in those days, it was de rigueur that the only movies that could get national awards would be from the stable of Art Cinema.

Till two decades ago, the tyranny of High Art dominated national film awards. So, when Karishma Kapoor, in 1991, won the National Film Award for Best Supporting Actress for her performance in the romantic drama Dil To Pagal Hai, all the hell broke loose. The Pioneer published an article on May 13, 1998, by Manojit Lahiri. In the article, a champion of Art Cinema said: “My God, is nothing sacred? Having corrupted the sensibilities of the youth, Bollywood, the sole manufacturer of opium for the masses, now must be laughing its head off. The impossible has happened! One of their ‘tinny’ stars of a mass-targeted mindless musical kitsch has picked up one of the nation’s most prestigious awards, sidelining, undoubtedly, several worthier talents from anti-glamour, pro-realism ‘other’ cinema. Shameful! To me, this marks a new low. From now on, I shall treat the National Awards as a huge joke.”

In the same vein, the Czarina of film criticism and Good Taste, late Amita Malik, said: “While I have nothing against Bollywood or mainstream cinema, I do genuinely believe that its induction and presence in the National Awards scenario is not quite sync with the philosophy, thinking or objectives of the body. The subjects, the treatment, the concerns—Bollywood represents a kink of cinema that goes totally against the very basics of what is propagated here. It’s not a question of good or bad but whether it is appropriate or compatible. It’s not.”

Come to think of it, the forebears of the champions of tolerance could not even tolerate the cinema that millions in this country love as a contender for national awards! What snobbery! What superciliousness! She wanted the jury to simply exclude what was not “appropriate or compatible,” she and her ilk being the arbiters of appropriateness or compatibility. That was then.

Much sewage has flown down the Yamuna in the last two decades. One of the very few things that have happened in this period is the decline, if not the demise, of the lal salaam film critic.

Indeed we have come a long way.