Liberty in India, RIP

Ravi Shanker Kapoor | March 18, 2017 6:54 pm

The right to freedom of expression, though enshrined in Article 19 of the Indian Constitution, is increasingly shriveling in our country. From the men and women who are expected to uphold the law and the Constitution, including Article 19, to goons and moralizers, everybody is itching to end liberty. In such a milieu, one wonders if free speech and expression would survive in India at all.

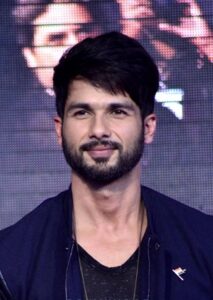

So, a filmmaker is assaulted, repeatedly threatened—and the authorities look the other way. And there are Muslim clerics offering unsolicited advice to the upcoming singer Nahid Afrin that she should stop performing in public. It is easy to decide which incident is more disgraceful: the Padmavati incident is more disturbing. Here, the Bharatiya Janata Party-ruled states are shamelessly allowing goons and scoundrels to intimidate creative persons. The mad mullahs, on the other hand, don’t need much state backing to further their perverse agenda; the duplicity of liberals and the so-called moderate Muslims (supporting free speech in the case of M.F. Hussain and opposing it when books by Salman Rushdie and Taslima Nasreen are in question) emboldens them to impose the medieval values on Muslim society.

We have a situation that the Rajasthan government, instead of punishing those who attacked the film director Sanjay Leela Bhansali in Jaipur a few weeks ago, has asked to come to terms with his tormentors, to placate them, to submit them! Not only are the goons not brought to justice, they themselves are elevated to the status of a court of justice. The hoodlums, claiming to be members of a little-known organization, the Shri Rajput Karni Sena (SRKS), destroyed the Padmavati film set and thrashed Bhansali in Jaipur.

Apparently, government inaction has encouraged other goons. There was another attack on Tuesday when 50-60 unidentified men set afire an under-construction set at Kolhapur. They also fought with about 20 security guards around the set.

All such because some busybodies felt that Bhansali was trying to malign Padmavati whose very historicity is dubitable. Padmavati or Padmini, a legendary 13th-14th century Rajput queen, finds the earliest mention in Padmavat, an epic poem written by Malik Muhammad Jayasi, over two hundred years after she was supposed to have performed jauhar, the act of self-immolation to save honor. She was Chittor king Ratan Sen’s wife. A woman of exquisite charms, the accounts of her beauty traveled far and wide. Which, according to the epic poem, proved to be calamitous for her, her family, and her kingdom. Alauddin Khilji, the Sultan of Delhi, got obsessed about making her and successfully campaigned against Chittor, which was razed.

Bhansali’s rendition of the legend, claims SRKS, lessens the depravity and wantonness of Khalji. They allege that there is even a scene of Padmavati and Khilji making love—something that the SRKS can’t stand.

There are several aspects to the controversy. First, Bhansali has the right to express through cinema. The SRKS or any other private body should not be allowed to punish Bhansali.

Second, cinema is not history; it does not alter the past. Mughal-e-Azam, for instance, has the look and feel of history, but it is pure fiction; there was no Anarkali (or, at least, like the one shown in the movie); Salim or Shekhu did rebel against his father, the Emperor Akbar, but the reason was power, not love. This, however, does not mean that Mughal-e-Azam or other such films should be banned.

Third, Khalji was a mass-murderer; no amount of sophistry can change this fact. If a moviemaker still tries to glorify Khalji, as Bhansali is alleged to be doing, he would be exposed as a stupid director. If Bhansali and others want to do that, they should be allowed in their ventures. Let film critics, historians, and cinegoers—but not violent activists—decide their fate.

Another, and a very disturbing, feature of the controversy is that often the focus of the issue gets replaced with secondary and bogus matters. For example, even decent people start discussing questions like ‘is Bhansali really showing Padmavati and Khalji getting intimate,’ ‘should a filmmaker be allowed to take liberties with history,’ and ‘did Padmavati really exist.’ The real issues—that a group of people indulged in violence, proudly flaunted their felony, and did not attract legal action—are being generally ignored.

Similarly, in the case of the singer Nahid Afrin, public intellectuals have been aghast at the temerity of Muslim clergy; some Muslim figures have pointed out that the Quran and Islamic doctrines do not proscribe music, so the fundamentalists’ zeal to banish it is misplaced. But, again, the issue is not what Islamic scriptures prescribe or proscribe; the issue is what is in sync with modernity. Anything that flies in the face of the modern value system and our Constitution should have no place in the 21st century India, be it the tetchiness of SRKS hoodlums or the petulance of mullahs. But, unfortunately, these are folks who are calling the shots. Consequently, freedom is having a hard time.