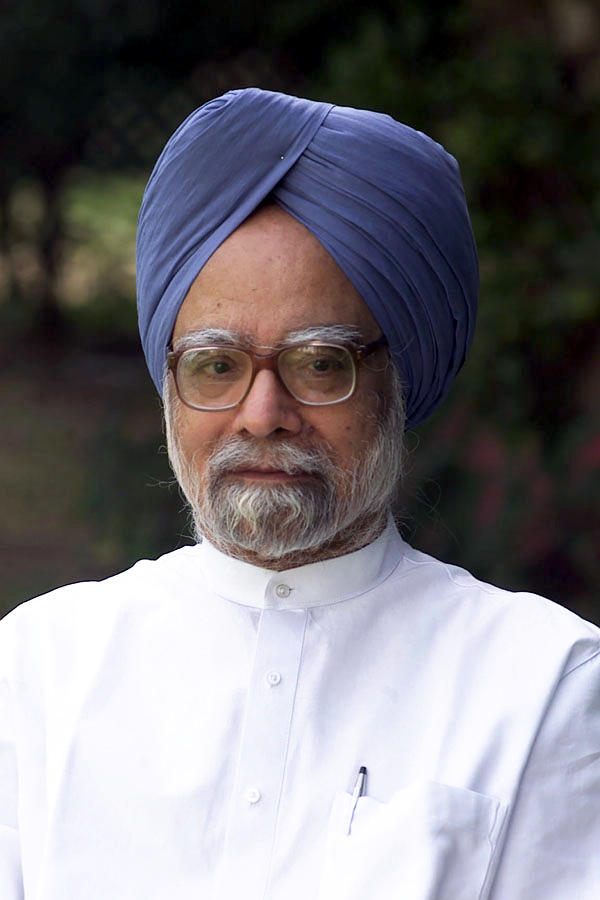

That former prime minister Manmohan Singh was a true gentleman is a truism. The excess of anything is bad; gentleness is no exception. Singh’s achievements were great. But these could have been greater if he had decided to hurt some people, if he had decided to be not too kind.

Singh’s reluctance to write his memoirs, as he told a reporter, stemmed from his concern that “the truth hurts, and I don’t want to hurt anyone.” This sentiment, though noble, invites scrutiny when considered in the context of his public service career. A memoir from a statesman of his stature is not merely a personal account; it is a valuable contribution to history, policy discourse, and public understanding of pivotal events. By refraining from sharing his perspective, Singh may have denied the nation a crucial resource for reflection and learning.

Memoirs offer unique insights that are often absent in official records. They provide context, motivation, and the human dimension behind policy decisions. Singh’s memoirs could have illuminated the impulses and reasons behind some of his most significant decisions like economic liberalization and the Indo-US nuclear deal. Steering the course of the economy when it was about to collapse, opening it up by discarding the worst features of socialism, unleashing entrepreneurship, laying the foundations of an economically stronger India—these were great feats. We deserve to know more about them.

Moreover, memoirs have the potential to correct misconceptions and address criticisms. Singh’s tenure has often been criticized for perceived policy paralysis during his second term, largely due to coalition politics and internal party dynamics. By sharing his side of the story, he could provide clarity and offer a nuanced perspective on the constraints he faced. This could not only have enhanced his legacy but also enriched public discourse on governance and leadership in a coalition era.

Singh’s concern that “the truth hurts” reflects the graciousness of his persona, his deep sense of personal integrity and empathy. It suggests an unwillingness to damage reputations or reopen old wounds. While such restraint is commendable, it raises questions about the balance between personal ethics and public responsibility. Leaders of his caliber have a duty to contribute to the collective understanding of their times, even if it involves uncomfortable truths. After all, history is often shaped by the candid reflections of those who lived it.

In a democratic society, transparency and accountability are fundamental values. Singh’s memoirs could serve as a tool for both, shedding light on the inner workings of governance and the complexities of policy-making. They could also inspire future leaders by highlighting the challenges and rewards of public service. By choosing to remain silent, Singh risks allowing speculation and incomplete narratives to dominate the discourse around his tenure.

By their very nature, memoirs reflect subjective interpretations and thus may not always present an unbiased account. While this is true, subjective perspectives are an inherent part of any historical narrative. They complement official records and academic analyses, providing a more holistic view of events. Singh’s memoirs would have been particularly valuable given his reputation for honesty and intellectual rigor.

It needs to be mentioned here though that his not writing his memoirs will doesn’t diminish his stature. As he himself said, history will be kinder to him than contemporaneity.