The Midwife’s Confession: Ugly reality, heroic endeavor

BBC documentary, The Midwife’s Confession, is the documentation (sans commentary) of an ugly reality of Indian society—female infanticide

Ravi Shanker Kapoor | October 2, 2024 9:56 pm

Amitabh Parashar

The most conspicuous aspect of the BBC documentary, The Midwife’s Confession, is that it is the documentation (sans commentary) of an ugly reality of Indian society. Its creator, Amitabh Parashar, has let facts tell a sad tale—or rather many a tale of female infanticide.

Parashar, who appears in the documentary, also directed it along with Syed Ahmed Safi. It may be some sort of record, as its making took almost three decades. He met a number of midwives—Siro, Hakya Devi, Dharmi Devi, and others. “I have been following Siro’s story for 30 years, ever since I went to interview her and four other rural midwives in India’s Bihar state in 1996,” he wrote about his journey on the BBC website (https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cvge858dvl5o).

These midwives were identified by a non-governmental organization as being behind the murder of baby girls in the district of Katihar where, under pressure from the newborns’ parents, they were killing them by feeding them chemicals or simply wringing their necks, Parashar wrote. “Hakiya Devi, the eldest of the midwives I interviewed, told me at the time she had killed 12 or 13 babies. Another midwife, Dharmi Devi, admitted to killing more—at least 15-20.”

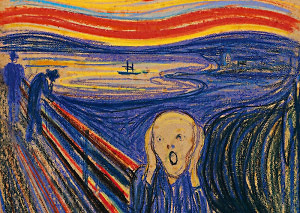

Female infanticide is something that any educated Indian would be familiar with—but just like they are also familiar with female feticide, poverty, malnutrition, and a variety of ills that afflict our country. These issues affect human beings, and yet they are so distant—as happening somewhere out there. The suffering is human, but at a safe distance from our emotions. These issues pertain to statistics rather than our sensitivities.

But the motion picture can animate statistics; it has the potential to bring human suffering from books and archives to our hearts and souls. “The death of one man is a tragedy,” said Josef Stalin. “The death of millions is a statistic.” This is how he tried to condone his own crimes of killing millions of people in forced collectivization and purges. One wonders if he could have been as blasé after watching Schindler’s List. In Spielberg’s masterpiece, the statistic of the slaughter of six million Jews by Hitler assumed a life of its own—a life that depicted death and unconscionableness in its starkness.

The Midwife’s Confession does something similar. Parashar gives female infanticide a face. Many faces actually—a rescued girl, her adoptive parents, the midwives, social workers. All of them tell the story of unspeakable cruelty and heroic compassion, of shocking social ills and brave, gutsy reformers, of sinning and redemption.

The documentary appears as semi-fiction, which has a prologue (an abandoned female infant noticed and rescued by a group of youngsters), the beginning, the unfolding of the narrative that culminates in a kind of catharsis for Siro, the protagonist. It has characters, Parashar the narrator being one of them.

It evokes a mix of feelings when midwives describe how they killed infant girls. In normal circumstances, one would feel nothing but anger and disgust at the culprits, but there was nothing normal with the parents and families of those unfortunate girls; they forced the midwives to do the dirty job. One pities rather than loathes the midwives who killed newborn girls. We don’t know if there were also any midwives who prodded the families of newborn girls to get rid of them by willingly offering their services, because the BBC documentary doesn’t have any such family interviewed.

A girl rescued by Siro. She is adopted by a couple in Pune, where she grows up as Monica Thatte. She was fortunate that the time of her birth was change began. “By the time I finished filming the midwives’ testimonies in 1996, a small, silent change had begun. The midwives who once carried out these orders had started to resist,” Parashar wrote. “This change was instigated by Anila Kumari, a social worker who supported women in the villages around Katihar, and was dedicated to addressing the root causes of these killings. Anila’s approach was simple. She asked the midwives, ‘Would you do this to your own daughter?’”

Sometimes, a few simple words can do what reams of expert opinion and sentimentalist baloney cannot. “Her question apparently pierced years of rationalization and denial,” Parashar wrote. “The midwives got some financial help via community groups and gradually the cycle of violence was interrupted. Siro, speaking to me in 2007, explained the change. ‘Now, whoever asks me to kill, I tell them: ‘Look, give me the child, and I’ll take her to Anila Madam.’ The midwives rescued at least five newborn girls from families who wanted them killed or had already abandoned them.”

The documentary has beautifully captured the pathos of the dramatis personae. This, however, comes at a cost. More facts about the subject of female infanticide—data on abandoned female infants, for instance—would have made it richer.

As I mentioned in the beginning, Parashar has let facts speak. The subject certainly gave him ample opportunity to pontificate, to burden the viewers with claptrap replete with formidable words like ‘patriarchy’ and ‘misogyny.’ But he refused to fall prey to the meretricious charms of political correctness. His sensibilities remain uncorrupted by any fashionable ideology.

This is what makes The Midwife’s Confession an excellent documentary.