Talibanization in India

Ravi Shanker Kapoor | November 20, 2017 11:08 pm

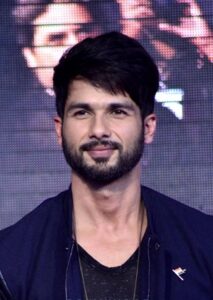

The controversy surrounding Sanjay Leela Bhansali-directed Padmavati underlines a disturbing fact about India: it is impossible for a filmmaker to freely make a history movie, or even a movie with a historical background. The Deepika Padukone-Ranveer Singh-Shahid Kapoor starrer may or may not be released, but the row has proved, if proof was needed, that the sphere of liberty is shrinking in our country. It has also unveiled for the nth time much that is unlovely in India.

In Rajasthan, Diya Kumari, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s MLA and a descendant of Jaipur’s former regal family, tweeted: “I will not allow any distortion of the valiant history of Rajasthan & Sacrifice of its people in fighting barbarians by movie #Padmavati.” Quite apart from the royal hangover (“I will not allow…”), there is the issue of distortion of history. But what, pray, is history? This is certainly not physics, the textbooks on which by different authors containing the same things about Newton’s laws. There are as many histories as there as historians. On India during the British Raj, for instance, eminent Leftist historians like Bipan Chandra have written books completely at variance with the ones written by equally eminent Niall Ferguson.

A filmmaker—for that matter, also a novelist or a poet—exercises his right to express himself when he makes a film on a historical subject or against a historical backdrop. Mughal-e-Azam, for instance, was a work of fiction, for the story—that Emperor Akbar’s son Salim, later Jahangir, revolted for a slave-girl Anarkali—has no grounding in history. So, should it never have been made? And, since it ‘distorts’ history, should its telecast be proscribed? Ditto with the Sunil Dutt-Vyajyanthimala starrer Amrapali.

The opponents of Padmavati claim that their views should be taken into account, or else… And we thought that there was the rule of law in the world’s largest democracy!

Even if a filmmaker were to bow to the demands of protesters, which views and how many views he could accommodate? Consider the curious case of Jo Bole So Nihal. In May 2005, the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) sought a ban on the film in which the hero, Sunny Deol, played the role of a Sikh cop. “The producer of the film has misused the holy Sikh community slogan (Bole So Nihal),” SAD chief Parkash Singh Badal told a press conference. “It is pertinent to mention here that a sub-committee of the Akal Takht had given a ‘clean chit’ to the Hindi film starring Sunny Deol,” said a PTI report on May 18. Badal’s statement was the result of intra-Akali bickering; some factions used the movie as a pretext to score brownie points.

Should a filmmaker go to every faction to seek their permission?

But his problems don’t end with the permissions; there can also be unpredictable objections, emanating from matters unrelated to the movie. In 2006, the film Fanaa was banned in Gujarat for a strange reason: the lead star, Aamir Khan, was against the Sardar Sarovar Dam built over the River Narmada and had demanded adequate rehabilitation for the ousted villagers!

A recent film, Baahubali, also faced similar problems because one of the actors had said something sometime back about some issue which had nothing to do with the film or its contents.

More dangerous than the machinations of professional protesters and unscrupulous politicians is the tacit and often explicit support they get from some thought leaders in the assault on freedom of expression. For instance, two prominent intellectuals on a television show supported the ban on Prakash Jha’s Aarakshan (2011). One of them justified the then UP chief minister Mayawati’s ban on the movie indicating that she was entitled to take whatever action she deemed fit for her political survival; any action for political survival was presented as if it were violence in self-defence, which is not illegal. The ideals and rights enshrined in the Constitution mattered little to the pro-Mayawati intellectuals.

In 1970, the Supreme Court justified censorship of films. The Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) was mandated to regulate cinema; but, as with any other government regulation, it too has acquired a life of its own. Even after the CBFC’s nod, which often requires unnecessary cuts, any political party, social outfit, cultural group, or publicity seeker can don the mantle of a censor and torment a filmmaker.

Creative freedom will remain constrained and restrained if the individual is deprived of the right to express himself or herself. Until the ever-proliferating constraints and restrains are removed, grumpy politicians, squeamish outfits, blackmailers, mischief mongers, and troublemakers will inexorably continue to thrive at the expense of freedom of expression. Especially that of filmmakers. The chilling effect is inestimable on creativity in general and filmmaking in particular. Today it is Padmavati, tomorrow it would be some other movie.