Give me liberty or give me… food!

Ravi Shanker Kapoor | August 5, 2017 6:56 pm

The Supreme Court has done well to trash the government’s argument that the imperative to provide food to citizens—and by implication to introduce any other welfarist measure—can undermine privacy and other basic fundamental rights.

Representing the Maharashtra government this week, senior advocate C.A. Sundaram buttressed the Centre’s stand that Aadhaar-related entitlements precede the right to privacy. “What is better—two square meals or right to privacy,” he asked.

What kind of democracy is this in which government can curtail or even abrogate a fundamental right at will? It is not just the official argument that is preposterous; the consequences are even more so. For if it is accepted, then what a government has to do to trump a fundamental right is just introduce an entitlement; and since entitlement will have primacy over fundamental rights, any of them could be abridged or even done away with. As if welfarism were a licence to trample upon the democratic rights and civil liberties of the people of India.

Thankfully, the apex court has dismissed this line of argumentation. Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, one of the Bench of the nine judges looking into the Aadhar versus privacy case, asked: “Does it mean the cherished constitutional rights are subservient to certain economic developments? Can two square meals be promised in return for barring people from protesting, forming association or giving up other fundamental rights? This can never be. We must guard against this tendency.”

The Supreme Court has to do a lot of guarding, for the political class is hellbent on crushing fundamental rights in the name of entitlements; typically, intellectuals and activists are also obsessed with entitlements.

Justice Chandrachud was not alone in slamming the government. Justice J. Chelameswar said, “It is a very cruel choice one can give to citizens—two square meals or right to privacy.” Justice R.F. Nariman also said: “In the era when personal liberty and fundamental rights are being given a wider meaning, how can you argue for contracting the width of fundamental rights?”

In a speech in February 1877, Lord Acton called liberty as “the delicate fruit of a mature civilization.” Among its enemies, he listed, among other things, “the strong man’s craving for power and the poor man’s craving for food.” In the Aadhaar case, however, it is not the poor man’s craving for food that has occasioned the debate on privacy; there has been no mass movement for food security. What the poor want is less, and not more, government—freedom from the visitations of cops, local authorities, etc. For them, government usually means trouble.

This is the reason that the poor don’t campaign for various entitlements; parlor pinks and professional radicals do that. And since entitlements invariably augment the size and scope of government, politicians love it: bigger state means bigger opportunities to patronize their flunkies, grab part of the taxpayer-funded largesse, and project themselves as the messiahs of the poor to boot. Sonia Gandhi was fond of activists because they provided the rationale for bigger state; the new dispensation too has found entitlements useful.

Whatever may be the pretensions of the Narendra Modi government—making a New India, making it Vishwaguru, the Indian Century, etc.—the basic instincts, thought processes, and modus operandi are conspicuously the same as those of the Congress regimes. The same statism, the same pathological love for welfare state, the same disregard for fundamental rights: ‘your body is not your body’, ‘two square meals are better than the right to privacy.’

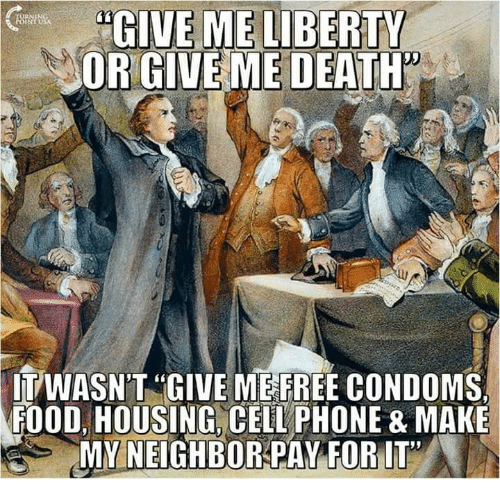

In a moving speech, an American founder and orator said, “Give me liberty or give me death!” To such eloquence, the Indian state’s response would be: we’ll give you food, forget about fundamental rights.