CBFC guidelines are real culprit

Ravi Shanker Kapoor | February 27, 2017 11:22 am

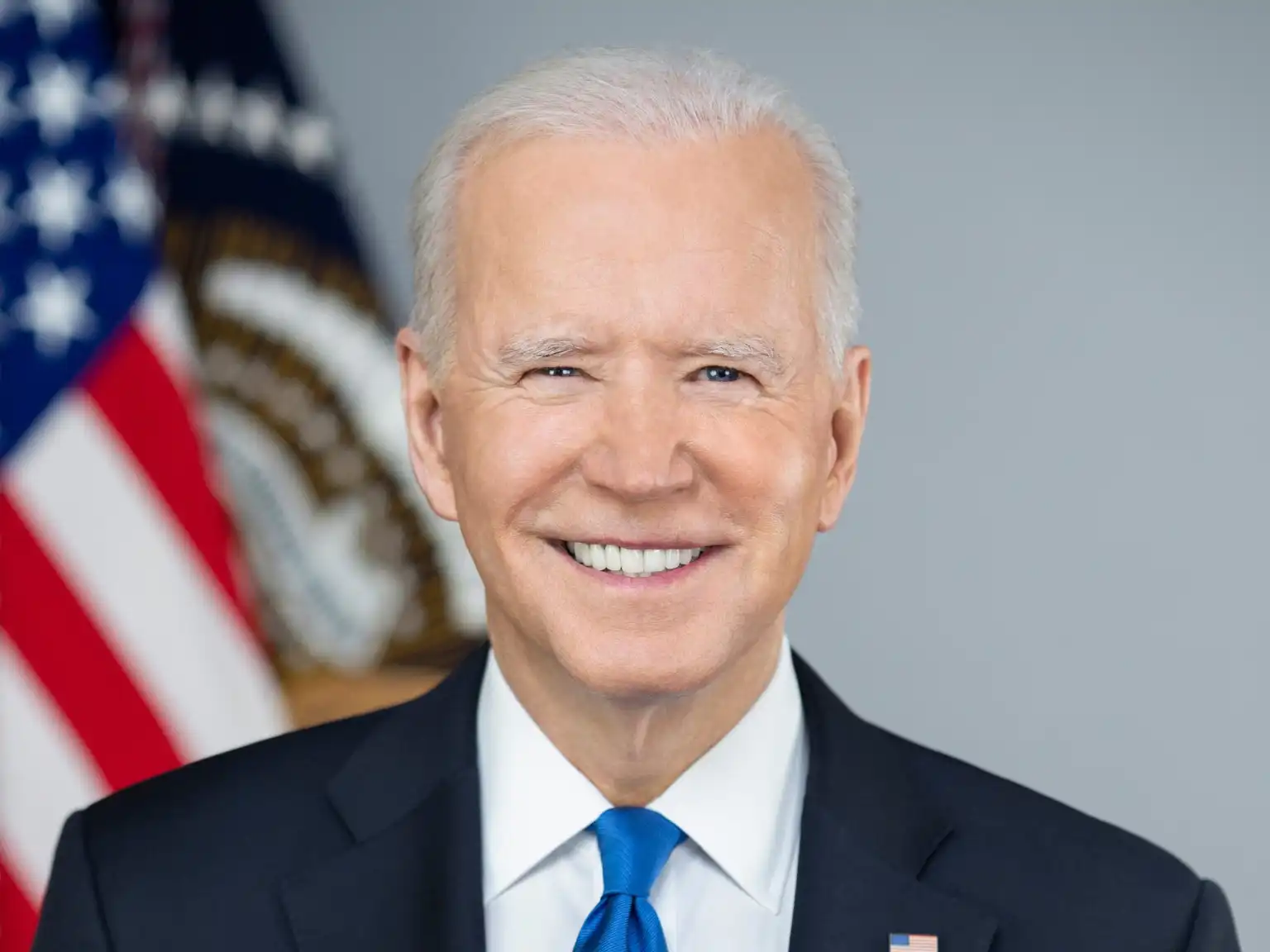

Indian Bollywood film producer Pahlaj Nihalani attends an event to honour politician and former finance minister Yashwant Sinha, who was conferred the Officer of the Legion of Honour in New Delhi earlier in the week, in Mumbai late on June 23, 2015. AFP PHOTO (Photo credit should read STR/AFP/Getty Images)

Pahlaj Nihalani never was so much in news when he was actually part of the film industry, making execrable movies, as he is now, enjoying a sinecure as the chief of the Central Board of Film Certification. He seems to have started enjoying his status as a Narendra Modi loyalist; he keeps making his obnoxious presence felt; this time he has found reason to be offended by a film called Lipstick Under My Burkha, to which he has denied certification.

His rationale: it is “lady oriented,” whatever it means, and contains “abusive words”; further, the movie apparently desecrates Indian culture. Nihalani told the media, “CBFC is part of the government, the responsibility of which is not only limited to issuing certificates to the films but also to preserve the culture and tradition of the country. CBFC is needed so that right kind of films are exhibited in public. The status quo will be maintained till the time I am here. We will follow the guidelines. I thank my staff members and officials who are sincerely and honestly complying with government rules.”

It is interesting to notice how a film certification body has arrogated to itself the responsibilities of the culture czar and the chief censor. It has been mentioned by film personalities that Nihalani, being the CBFC boss, can do certification only, that the word ‘censor’ does not appear in the abbreviation CBFC, that he and his officials should do only what they are mandated to do—film certification.

Well, the picture is a bit more complicated and problematic than Nihalani’s sanskari persona. He is actually right in saying that he is just following the guidelines. The CBFC’s guidelines, as mentioned in its website, quote the Cinematograph Act,1952, mention the reasonable restrictions on the right to freedom of expression as prescribed in the Constitution.

But the guidelines also teach moral science. So, a film should “not deprave the morality of the audience. Guidelines are applied to the titles of the films also.” Further, a film should remain “responsible and sensitive to the values and standards of society.” Doesn’t it expose an anti-honor killing film to censorship, for caste panchayats supposedly uphold “the values and standards of society”?

There is guideline mandating that “the medium of film provides clean and healthy entertainment.” Devdas drinks irresponsibly and visits prostitutes. Sahib, Bibi aur Ghulam, another classic, shows the debauchery and decadence of feudalism. Should they be banned?

The CBFC wants that “anti-social activities such as violence are not glorified or justified” and “the modus operandi of criminals, other visuals or words likely to incite the commission of any offence are not depicted.” Filmmakers should not have scenes “showing involvement of children in violence as victims or perpetrators or as forced witnesses to violence, or showing children as being subjected to any form of child abuse.”

These guidelines can be used to proscribe any crime thriller. That’s not all; there are more that empower CBFC officials to torment any filmmaker on any count. CBFC guidelines prohibit: abuse or ridicule of physically and mentally handicapped persons; showing cruelty to, or abuse of, animals; pointless or avoidable scenes of violence, cruelty, and horror; scenes of violence primarily intended to provide entertainment and such scenes as may have the effect of de-sensitizing or de-humanizing people; scenes which have the effect of justifying or glorifying drinking; scenes tending to encourage, justify or glamorize drug addiction; scenes tending to encourage, justify or glamorize consumption of tobacco or smoking.

While such activities are bad, they do exist in society. If a filmmaker doesn’t portray society, what else does he portray? Gods and goddesses? Mythological characters? (I have doubts, though, that even this would be objected to by the tetchy.)

Therefore, at the heart of the controversy are the CBFC guidelines which empower morality mobsters like Nihalani to play havoc with creativity. The removal of Nihalani is as imperative as the drastic changes in the guidelines. For the sake of creativity in cinema.