Remembering Gulliver as Republic of Laputa celebrates 67the anniversary

Ravi Shanker Kapoor | January 26, 2017 1:35 am

As India celebrates the 67th anniversary of it becoming a republic, it is instructive to take stock of its basic structure and defining feature. The exercise, however, doesn’t result in soothing observations.

The preamble to the Constitution said, “WE, THE PEOPLE OF INDIA, having solemnly resolved to constitute India into a SOVEREIGN, SOCIALIST, SECULAR, DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC and to secure to all its citizens:

JUSTICE, social, economic and political;

LIBERTY of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship;

EQUALITY of status and of opportunity; and to promote among them all

FRATERNITY assuring the dignity of the individual and the unity and integrity of the Nation;

IN OUR CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY this twenty-sixth day of November, 1949, do HEREBY ADOPT, ENACT AND GIVE TO OURSELVES THIS CONSTITUTION.”

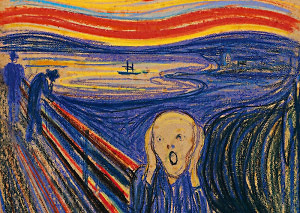

It is a well-known fact that the words “socialist” and “secular” were added later, but this is not germane to our discussion. What got constituted in 67 years is a gigantic laboratory in which politicians and intellectuals of various persuasions have tested their multifarious theories—to the detriment of the people. Indeed, we have got something that is very similar to, if not is, the Republic of Laputa.

Laputa, a flying island, was a kingdom that the protagonist of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels visited. The Laputans were veritable intellectuals, whose theories—as also in the contemporary world—had lost touch with the reality. A quintessential British conservative, Swift (1667-1745) has only disdain for the high-flown, untested ideas that theorists of all hues have always wanted to impose on society.

The consequences? “Their Houses are very ill built, the Walls bevil without one right Angle in any Apartment; and this Defect ariseth from the Contempt they bear to practical Geometry; which they despise as vulgar and mechanick, those Instructions they give being too refined for the Intellectuals of their Workmen; which occasions perpetual Mistakes. And although they are dextrous enough upon a Piece of Paper in the Management of the Rule, the Pencil, and the Divider, yet in the common Actions and Behaviour of Life, I have not seen a more clumsy, awkward, and unhandy People, nor so slow and perplexed in their Conceptions upon all other Subjects, except those of Mathematicks and Musick,” Gulliver notices.

He describes in some measure the misfortune of Lagado, the Capital of the nation Balnibarbi under the Kingdom of Laputa. “That about Forty Years ago, certain Persons went up to Laputa, either upon Business or Diversion; and after five Months Continuance came back with a very little Smattering in Mathematicks, but full of Volatile Spirits acquired in that Airy Region. That these Persons upon their Return, began to dislike the Management of every Thing below; and fell into Schemes of putting all Arts, Sciences, Languages, and Mechanicks upon a new Foot. To this End they procured a Royal Patent for erecting an Academy of PROJECTORS in Lagado: And the Humour prevailed so strongly among the People, that there is not a Town of any Consequence in the Kingdom without such an Academy. In these Colleges, the Professors contrive new Rules and Methods of Agriculture and Building, and new Instruments and Tools for all Trades and Manufactures, whereby, as they undertake, one Man shall do the Work of Ten; a Palace may be built in a Week, of Materials so durable as to last for ever without repairing. All the Fruits of the Earth shall come to Maturity at whatever Season we think fit to chuse, and increase an Hundred Fold more than they do at present; with innumerable other happy Proposals. The only Inconvenience is, that none of these Projects are yet brought to Perfection; and in the mean time, the whole Country lies miserably waste, the Houses in Ruins, and the People without Food or Cloaths. By all which, instead of being discouraged, they are Fifty Times more violently bent upon prosecuting their Schemes, driven equally on by Hope and Despair.”

There were many more experimentations like changing human excreta back into food and extracting sunbeams out of cucumbers.

The “volatile spirits” of Laputans that Gulliver mentioned spring from enthusiasms. In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, John Locke (1632-1704) discussed enthusiasm at some length. He defined “enthusiasm [as] which, though founded neither on reason nor divine revelation, but rising from the conceits of a warmed or overweening brain… For strong conceit, like a new principle, carries all easily with it, when got above common sense, and freed from all restraint of reason and check of reflection, it is heightened into a divine authority, in concurrence with our own temper and inclination.”

Enthusiasm, Locke writes, accepts its supposed illumination without search and proof. “…the love of something extraordinary, the ease and glory it is to be inspired, and be above the common and natural ways of knowledge, so flatters many men’s laziness, ignorance, and vanity, that, when once they are got into this way of immediate revelation, of illumination without search, and of certainty without proof and without examination, it is a hard matter to get them out of it. Reason is lost upon them, they are above it: they see the light infused into their understandings, and cannot be mistaken…”

It is not surprising that Locke’s description of enthusiasm brings Jawaharlal Nehru and Narendra Modi to mind. Both are equally guilty of intellectual laziness, ignorance, and vanity.

Nehru fell so badly the meretricious charms of socialism that he not only set up public sector undertakings, which remain a burden on the exchequer and people, and strangled the economy with excessive regulation, but also favored collectivization of agriculture. This despite the proven failure of the policy in Stalin’s Russia—precipitous fall in production and the death of millions.

His daughter was not doctrinaire but, being politically unscrupulous, had no compunctions in allying with Leftists and, because of their undue influence, adopting policies like bank nationalization that badly hurt the economy. Then there was V.P. Singh—inarguably the worst prime minister our country has suffered—who was so enamored with the pathology called social justice that he willfully divided the society.

Then there was Sonia Gandhi, whose contempt for facts and reason knew no bounds. At a time when international credit rating agencies were contemplating downgrade for India, she forced the Manmohan Singh government to for the disastrous food security law.

Modi’s demonetization also has the stamp of Laputa. So great is his enthusiasm for untested ideas and his desire be “above the common and natural ways of knowledge” that he announced a measure which has done immense harm to the economy and the poor, while its beneficial consequences, if any, remain in the realm of speculation.

In the last 67 years, a politician-intellectual complex has come into being: while intellectuals create a climate of opinion for state intervention in the economy, politicians capitalize on the frenzy that thought leaders work up. Politicians and intellectuals get into a symbiotic relationship at the expense of people. This complex promotes and supports dirigisme in its variegated manifestations, be it the socialistic pattern of society, bank nationalization, the Mandal Commission report, rapid proliferation of entitlements, or demonetization.

Right from the experiments and enthusiasms of Nehru to those of Modi, India has suffered all manner of stupidities, resulting in lower growth, stultified development, pathetic law and order, sclerotic administration, rickety justice system, and weakened national security. And, not to forget, we are a Fundamental Right, the Right to Property, fewer and another, the Right to Freedom of Expression, severely curtailed.

In the last 67 years, we have seen India becoming the republic of Laputa.