How blind a nation can get? That is the question that comes to mind watching Amitabh Parashar’s documentary film, Eyes of Darkness.

Every educated person has heard about the infamous Bhagalpur blinding atrocities that were carried out in a series of incidents in 1980 and 1981 in Bihar. The outrage was perpetrated by policemen against 33 individuals under trial, some of whom were petty criminals. It became international news in the early 1980s. Prakash Jha even made a successful feature film on the subject, Gangajal. What few know, however, is that the blinding cases did not end but began in Bhagalpur. While cops in the district or elsewhere never indulged in this practice again following widespread outcry, mobs in Bihar adopted this cruel method of crime control—at least to punish petty criminals from poorer sections. And mobs have persisted with it till date.

Yes, in this day and age, when every politician of every hue and every stature—from Hindutva votaries to comrades, from Prime Minister Narendra Modi to the local neta—loudly display their love for the poor, the oppressed, et al. At the same time, they keep their eyes shut to the human rights violations the poor suffer every day, lynching and blinding by mobs being the most egregious among the violations. It is the acquired blindness of the powers that be that infuriated me while watching Eyes of Darkness.

A boy, barely out of teens, is blinded because he dared to ask for full wages as agreed upon from his employer. Raju Alam, a 20-something, lost his eyes owing to an intra-community dispute. The 24-year-old Madhepura farmer Ajay Yadav met the same fate on November 15. “The targets as well as the perpetrators of blinding by mobs are from the so-called backward and lower castes. The victims are invariably poor people, some of them petty criminals, even teenagers. It is not that the authorities are unaware of such brutalities. The police and administration refuse to acknowledge the monstrosity of such incidents. They haven’t taken any concerted action to eradicate this inhuman practice,” says Parashar.

The menace is just not on the radar of those who matter; for our political masters and top bureaucrats and cops, it is almost something inconsequential, almost as if blinding incidents happen in, say, Somalia or Sudan, somewhere out there which is far away from our world. But this unspeakable crime does happen in our world, our country, mostly in Bihar, a politically important state.

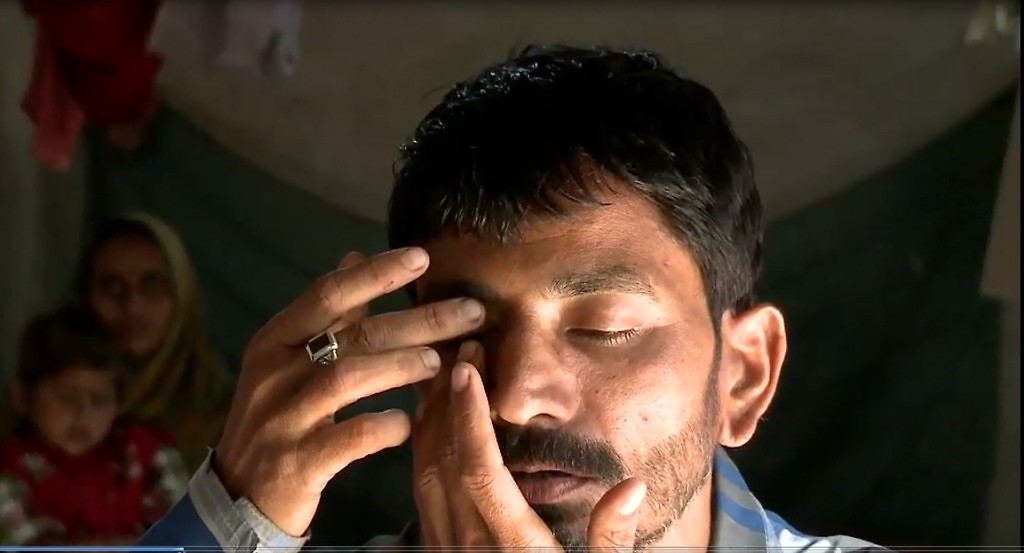

Munna Thakur, a resident of Hingana village in Raniganj, is kind of protagonist of the film. Every saint, they say, has a past; every sinner, a future. Thakur, who led a life of crime till 2010, sought a simple and peaceful, if not saintly, life. He surrendered before the law and, after serving a four-year sentence, and hoped to live the life of a law-abiding citizen. He fielded his wife Indu Kumari for the village chief’s by-election, which led to heightened tension and finally resulted in his and his friend’s blinding. “They injected an acid-filled syringe in my eyes. Only after they saw blood oozing out that they let me go. It was the shock of my life to realize that I won’t be able see anymore. It would have been better had they killed me,” says Thakur.

That was not the end of his ordeal. Apart from his struggle to make both ends meet and bring the culprits to justice, he is worried about his son. The boy fears going to school, as one of the teachers is among the accused who blinded Thakur. This is disconcerting for the father. The film ends with Thakur taking his child to school.

Isn’t it astonishing that the media—despite stupendous growth and expansion in the last few decades—has failed to discern the vile trend that Parashar has portrayed? There are thousands of journalists from Bihar in various media organizations, yet none of them found anything unusual in the cases of mob blinding. Parashar could find nine such cases in 2016; for every year since 2012 a similar number of cases have been reported. Sanctimonious speeches of politicians are big news; the innumerable turns and twists of the Yadav family hit front pages of papers; but poor people losing eyesight to mob justice is not something any news channel devoted a programme to.

In fact, Eyes of Darkness holds a mirror up to the entire nation. For dehumanization, like the truth, involves us all.

Pictures: Munna Thakur (top) and Amitabh Parashar