In the wake of the demonetization, a few simple facts have been brushed under the carpet, one of them being that black money has several shades. Treating every untaxed rupee as black, and overlooking its various shades, is grossly unfair and unjust; it is also a red herring.

Black money can be categorized under two broad categories: legally earned but tax-evaded income, and ill-gotten wealth by way of bribes, drug and human trafficking, gun-running, kidnapping, extortion, etc. Treating the two kinds as just the same is moral equivalence—an affliction that invariably has consequences.

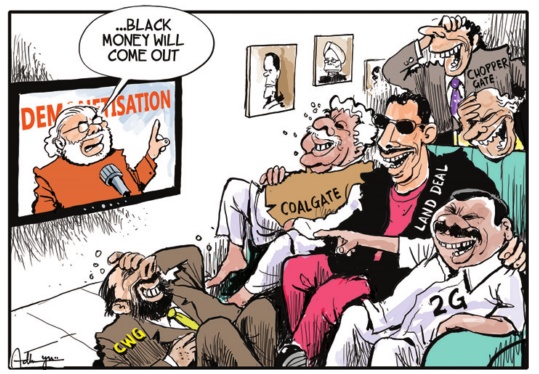

Whatever happened to the lakhs of crores of rupees that are stashed in Swiss banks and tax havens? That’s what the Bharatiya Janata Party used to tell us. What about the promises that that money would be brought back to India? What about the corrupt going to jail? What about the follow-up action against the scamsters who flourished during 10-year UPA rule? The media, Rajya Sabha member Subramanian Swamy, and a few activists have brought scandals to the fore, but the saffron party hasn’t; nor has the BJP government at the Centre done anything that gives any indication that the crusade against venality has moved an inch.

This is not to say that Prime Minister Narendra Modi has done nothing to clean up the system, or that he doesn’t have the guts to take bold decisions; the demonetization is indeed bold, even though its efficacy and even legality are questioned. A large number of administrative steps have been taken. But all these measures are prospective, not retrospective; these are intended to curb corruption in the future; but, unfortunately, little has been done to penalize those who were involved in sharp practice, fraudulence, and worse in the past.

Even within the category of tax-evaded black money, there are two kinds of offenders—big businessmen who pay partial income tax, and millions of people whose annual earnings are above the taxable limit of Rs 2.5 lakh per annum but who don’t pay any income tax because they deal mostly in cash. Which means that as the role of cash decreases in our economy becomes and more traceable transactions are carried out, a very large number of lower-income people would come under the income-tax net.

This will be very unfair to the people earning Rs 2.5 lakh-Rs 10 lakh per year. The main reason is that in our country the income-tax exemption limit is very low. In the UK, for instance, a person earning 11,000 pounds, or Rs 940,000, per year pays no tax.

It seems that the lower middle class would bear the burden of the so-called crusade against black money. The big fish, with the huge caches in foreign banks, are untouched by the crusade; the major domestic evaders are partially hit. But the real victims would be the folks who just manage to cling to a modest lifestyle—sending kids to some variant of ‘English medium’ school, once-in-a-month visit to a shopping mall with dinner at the food court, a two-wheeler or even a worn-out automobile, perhaps a visit to Vaishno Devi or Shimla once in a while.

Interestingly, a lot of Modi-bhaktas are found in this economic grouping. Such, however, is their fervor and their admiration for the Prime Minister that they tend to ignore all such obvious facts. Given the length of queues outside banks (leading to scores of deaths), the misery the man on the street has been subjected to, and the disruption it has caused to the economy, especially the informal sector, it is conspicuous that there have been no riots and law-and-order problems. In a country where people get killed over trifling matters like parking, the fact that so many have willingly borne so much inconvenience without protesting suggests that Modi enjoys huge support from all sections.

But for how long? I don’t think anybody has any answer to this question. Nor, for that matter, is anybody sure as to what kind of impact the demonetization would have in the long run not only on the economy but also on politics and society. As it is, very few jobs are getting generated, despite India being the fastest growing major economy. What would happen when even the GDP growth slows down?

Further, while the informal sector is worst affected, the prospective investor is unlikely to be enthused by the sudden decision to pull out 86 per cent of the currency. If there is anything that businessmen hate and dread, it is unpredictability and abrupt changes in policy, tax rates, etc. As it is, not many are investing in our country.

It is true that at present Modi enjoys huge support among people, for they believe that he has taken a concrete step. But this support may evaporate fast if the consequences prove to be too severe and persist for too long. The Prime Minister and his advisers would do well to remember that Indira Gandhi too was at the peak of her popularity in 1972 because of the populist-socialist decisions like bank nationalization she had taken and her victory in the Indo-Pak War 1971. But socialism, along with oil shocks, played havoc with the economy and, consequently, her government’s popularity. She had to resort of draconian measures, which further alienated her from people. The denouement was 1977.

Modi should beware that the present success doesn’t become a trap for him.

Picture courtesy: The Times Of India