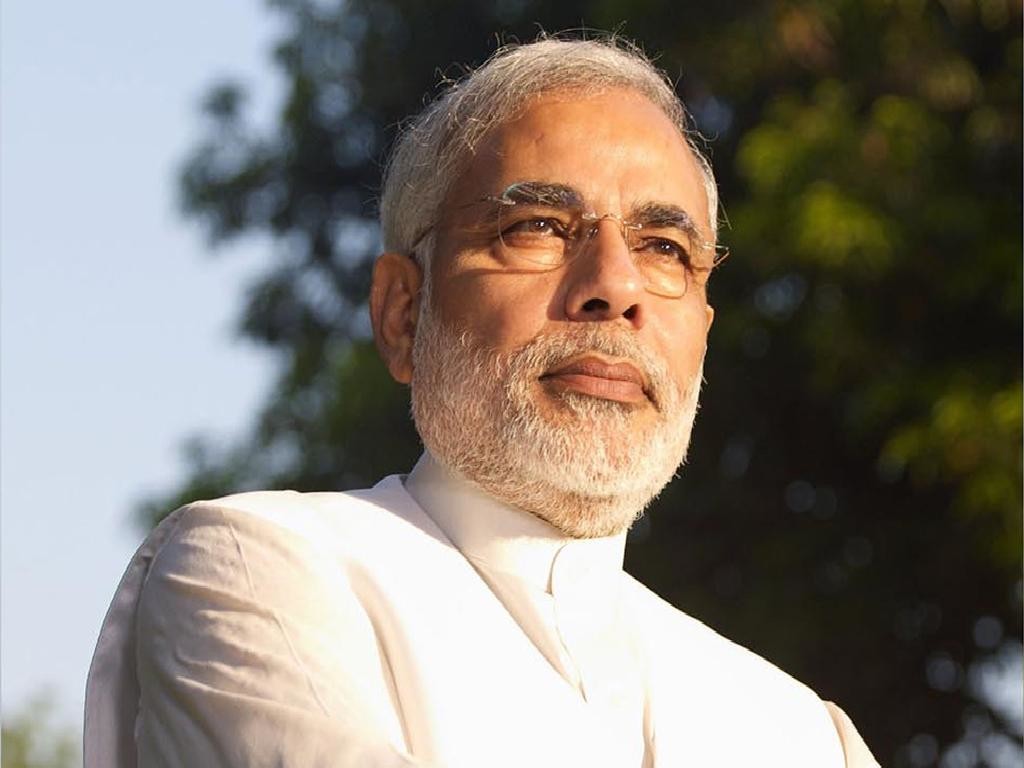

The Narendra Modi regime seems to have forgotten the poll promise of maximum governance-minimum government; the reverse seems to be the reality. A new government proposal that there would be an “anti-profiteering” clause in the revised draft model goods and services law is a testimony to the Prime Minister’s newfound love for socialism.

The dirigiste dispensation wants to ensure that “businesses pass on any benefit of reduction in tax rates to consumers, a move aimed at checking any spike in prices of commodities as a result of the rollout of the ambitious tax reform measure” (The Times Of India, November 27). The powers that be want to eliminate or minimize profiteering.

To be sure, the very word ‘profiteering’ reeks of statism. Cambridge Dictionary defines it as “the activity of taking unfair advantage of a situation to make a large profit, often by selling goods that are difficult to get at a very high price.” How on earth anybody—least of all, politicians and bureaucrats—can know whether or not a product or service is making “a large profit”? What is a large profit?

A shopkeeper spends Rs 200 making a shirt, or procuring from some other firm, and sells it for Rs 1,000. Is it profiteering? On the face of it, the answer is in the affirmative, for 400 per cent margin indeed appears high. But what about the rent he pays for the shop, the overheads he incurs, the salaries he pays to salespersons, the money he spends on advertising, and so on? And what happens to the residual stock which is often dispensed at throwaway prices?

All these concerns are far from the minds of the politicians and bureaucrats at the helm. So, the revised draft model GST legislation has provisions for an authority to “examine whether input tax credits availed by any registered taxable person or the reduction in the price on account of any reduction in the tax rate have actually resulted in a commensurate reduction in the price of the said goods or services supplied by him.”

Typically, the authority will have the power to impose penalty, “as may be prescribed in cases where it finds that the price being charged has not been reduced.”

Needless to say, the new provision is a recipe for procedural bottlenecks, unnecessary paperwork, and corruption. For it will encourage all manner of controls, bureaucratic micromanagement, and unwarranted governmental intervention in economic activity.

The Bharatiya Janata Party’s 2014 election manifesto said, “We shall wipe out the problems of poverty and backwardness by… policies aimed at fully harnessing India’s productive potential and creating national wealth; by policies that ensure distributive justice by expanding the basket of opportunities for all; by policies that direct greater governmental investment and incentivize more private investment in backward and rural areas; by policies and programmes that bring vibrancy to the rural economy, expand and deepen rural markets, and thus create large-scale employment and self-employment opportunities locally…”

The anti-profiteering clause will surely be cheered by the legions of Modi-bhaktas; the Prime Minister would be further lionized as the champion of the poor and the scourge of the unscrupulous. That it will play havoc with the endeavor to improve the ease of doing business in India is of little concern to the devotees; after all, devotion, especially in worldly affairs, is a sentiment bereft of rationality. It is time the BJP government took recourse to rationality in the affairs of the economy.

Socialism populism, like steroids, may prove beneficial for the party in the short run—Assembly elections in UP, Punjab, etc. But Modi should aspire to become a statesman, who thinks about the next generation, and not a politician, whose solitary concern is the next election.