The European Commission’s decision that Apple should pay $14.5 billion of corporate income taxes to Ireland as reimbursement of illegal state aid has many interesting dimensions. The most important from India’s perspective is Ireland’s refusal to accept the gigantic sum from the top technology company headquartered in Cupertino, California.

According to the European Union’s Treaty on the Functioning, private enterprises and state-owned companies are barred from government subsidies. The subsidies include fiscal sops to specific companies, which is categorized as a specific multinational is state aid. The European Commission, however, doesn’t corporate tax rates in EU member-states, which vary from 33 per cent to 12.5 per cent Ireland.

The products Apple sells in Europe are manufactured in China, but their value is the result of the intellectual property that is owned by Apple’s US parent. By a curious financial and accounting jugglery, which was accepted by Irish authorities, Apple ensured that it paid only a fraction of the due amount to the taxmen in Ireland. So, in 2014, the tech behemoth shelled out tax at the rate of 0.005 per cent in Ireland; for every million dollar it earned as profit, it paid only $50.

A press release issued by the European Commission said, “Under the agreed method, most profits were internally allocated away from Ireland to a ‘head office’ within Apple Sales International. This ‘head office’ was not based in any country and did not have any employees or own premises. Its activities consisted solely of occasional board meetings. Only a fraction of the profits of Apple Sales International were allocated to its Irish branch and subject to tax in Ireland. The remaining vast majority of profits were allocated to the ‘head office,’ where they remained untaxed.”

A ‘head office’ which exists in no country and is without any employees—this is indeed surreal. And we thought all along that accountants are unimaginative creatures!

Be that as it may, the big question is: why is Ireland reluctant to ask for $14.5 billion which, with interest, can go up to $19 billion? These are big numbers, especially for a small country; $14.5 billion is 5 per cent of its gross domestic product or GDP. The prospects of retirement of public debt, which is 94 per cent Ireland’s GDP, should have delighted Finance Minister Michael Noonan? So, why is he keen on appealing against the European Commission’s ruling?

The answer is simple: he does not want to dent the image of his country as an attractive investment destination. Accepting $14.5 billion is an easier, politically beneficial option, but the Irish government doesn’t seem inclined towards it. It’s not that everybody in Ireland wants to forego the huge amount. Opposition parties like Sinn Féin are against appeal but they are not accusing, a la Kejriwal, that Noonan is on the payroll of Apple.

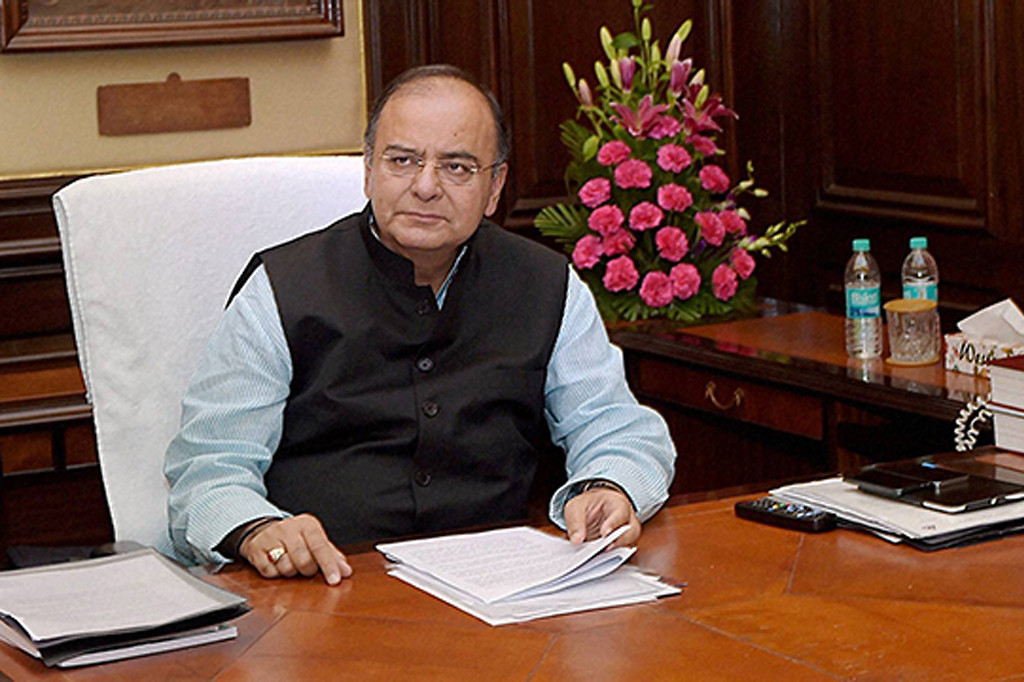

Now compare this situation with the infamous Vodafone case where the Congress-led government disregarded the country’s apex court in January 2012 for a smaller amount, triggering the charges of tax terrorism. In fact, it is wrong to blame only the United Progressive Alliance for smearing the country’s reputation. More than four years later, in April this year, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley insisted on extracting money from Vodafone. “Why should the government not file an appeal when it thinks that it is an appealable order,” he told a news channel. “There is no company in the world that is immune from paying taxes.”

At the heart of the Vodafone issue is the Finance Ministry’s objective of revenue maximization. Unfortunately, that is the prime, if not the sole, objective of the ministry. Business climate, investor sentiment, the country’s image as an attractive investment destination, propriety (respect for the judiciary), the rule of law—all these are marginally important for FinMin, perhaps because they are intangible. Money, however, is tangible; it can be used to tom-tom the rashtrawadi government’s immeasurable commitment to the nation. ‘We got thousands of crores from a multinational corporation which the Congress couldn’t.’

It is not politics eclipsing economic policy, for Noonan is also a politician, yet he compares the acceptance of $14.5 billion with “eating the seed potatoes and destroying the future for people for short term advantage now.” India’s obstinate attitude is actually reflective of the most dangerous and myopic form of politics triumphing over sound and prudent economic policy.

It is time the Finance Ministry got its priorities right: revenue maximization should never be the policy; focus should on decontrol, greater ease of doing business, and elimination of procedural rigors; this would result in brisker economic activity, more jobs, and general prosperity. In fact, all this would augment revenue. Revenue maximization is serendipity, for in economic policy the longest distance between two points is the straight line.

Unfortunately, dharma and karma are vanishing from our country. Government should work for the wellbeing of people; it is into revenue maximization and organizing jamborees. Pontiffs should be offering good counsel to people; they are running FMCG companies and making films. Filmmakers, on their part, often don the mantle of spiritual gurus and adulterate cinema by delivering messages for society (see Filmmakers, say no to message, https://thehinduchronicle.com/2015/04/filmmakers-say-no-to-message/). Nobody is doing what they ought to be doing, and doing instead what they shouldn’t be.

The sanskari government should learn the pertinent lessons from the doctrines of dharma and karma. And Jaitley from Noonan.