New Punjab law shackles mind

Ravi Shanker Kapoor | March 24, 2016 11:06 am

The Punjab Assembly’s nod to the Indian Penal Code (Punjab Amendment) Bill, 2016, that seeks life imprisonment for sacrilege of the Guru Granth Sahib, is a serious attack on both free speech and religious freedom. The anti-blasphemy law also brings us close to such illiberal nations as Saudi Arabia and Pakistan.

The legislation adds Section 295AA to the IPC, enhancing the punishment under Section 295—injuring or defiling place of worship with intent to insult the religion of any class—from two to 10 years. That the Bill was passed unanimously underlines the fact that liberty has few devotees in this part of the world. In fact, Leader of the Opposition Charanjit Singh Channi wanted to increase the scope of the legislation; he sought augmented punishments for disrespect to all religions. His party colleague, Congress MLA Tarlochan Soondh, was also of the same view. The amendment for extension was rejected, though. We are grateful for small mercies.

As it is, Section 295A of the Indian Penal Code militates against the spirit of liberal democracy. It reads as: “Deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs.—Whoever, with deliberate and malicious intention of outraging the religious feelings of any class of [citizens of India], [by words, either spoken or written, or by signs or by visible representations or otherwise], insults or attempts to insult the religion or the religious beliefs of that class, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to [three years], or with fine, or with both.”

The problem with feelings, religious or otherwise, is that they are subjective, while laws are predicated upon objectivity; this is one reason that Section 295A is so controversial. The words, signs, and actions of a person may outrage Mr. X’s feelings but they may not offend, or even disturb, a large section of Mr. X’s coreligionists.

This is the reason that Bharatiya Janata Party leader Subramanian Swamy has challenged hate speech laws, including Section 295A, in the Supreme Court. He said that several provisions of the Indian Penal Code dealing with offences of “hate speech” violate the Fundamental Right to freedom of expression as enshrined in the Constitution. He has rightly asserted that these legal provisions are used to penalize the citizens of India in the exercise of their right to freedom of expression and, there, should be invalidated.

If accepted by the apex court, this invalidation would be one of the biggest victories for liberty in India in the last one hundred years, to be ranked alongside Justice H.R. Khanna’s note of dissent in 1975 that upheld fundamental rights against the deluge of Indira Gandhi’s tyranny. For the so-called anti-hate speech restrain the mind. “All these sections do not have any safeguards within which a person can publicize his analysis of various nuanced truths of interaction between groups which differ on the basis of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, caste or community,” Swamy said in his petition.

The governments in Independent India should have provided the needed safeguards to uphold the cause of liberty, but they did the exact opposite. Right from the beginning, our political masters tried to shrink rather than expand the sphere of liberty. The very first Amendment to the Constitution introduced “reasonable restrictions” on freedom of expression. The purpose was to ban or subdue anything opinion, whether on the Left or the Right, that was unfavorable to Jawaharlal Nehru, the self-righteous megalomaniac who considered himself to be the repository of all wisdom.

Unfortunately, our Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Section 295A in 1957. Even eminent jurists defend this obnoxious section. In an article in The Indian Express (June 25, 2006), former attorney general Soli J. Sorabjee wrote, “The yardstick [to determine whether or not something is scurrilous] is not the standards of hyper-sensitive and volatile minds but those of ordinary persons of normal sensibilities.”

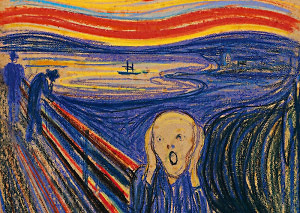

This is an argument to shut the mind of a community or country to questioning, imagination, and innovation. Had Lord Bentick applied the yardstick of the minds “of ordinary persons of normal sensibilities,” he could not have banned suttee in 1829; in fact, this yardstick would have banished all social reform. Had Galileo been bothered about the sensibilities of ordinary persons, he would never have started his scientific journey. The march of civilization is predicated upon breaking the chains of ordinariness.

In a nutshell, the Indian nation, the Indian state, the eminent people of India, almost everybody who is somebody in our country has undermined the concepts of individual liberty and freedom of expression. Free speech has been downgraded considerably over the decades because of hurt feelings, political expedience, or downright mischief. And few are bothered.

So, it is not surprising that while the powers that be should have been striving to scrap the notorious Section 295A, they are working to make it even more draconian. For the fear is that other states, and even the Centre, may follow suit.