How Gandhi ensured India’s enslavement

Ravi Shanker Kapoor | October 2, 2015 1:15 pm

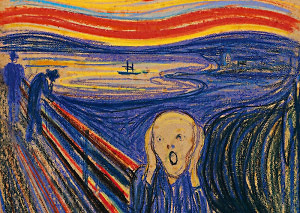

Mahatma Gandhi

We have been tutored to venerate Gandhi as a great philosopher, as the embodiment of nobility, profundity, and wisdom. Perhaps he was a good human being. It is, however, indubitable that his intellect was of a very low caliber. V.S. Naipaul might have exaggerated when he called him an uneducated kind of man, but he was certainly not a philosopher.

With the rise of Gandhi in Indian politics, all that was rotten in our country—social rigidities, shutting of the mind, civilizational sloth, entropy, et al—came to the fore. Before him, the nationalist movement was conducted in, more or less, rational terms—ending racial discrimination, more representation of Indians in administration, protecting economic interests of Indians, social reforms, etc. The leaders led the people, spread such universal ideas as individual liberty and limited government that they had imbibed from the British, worked for the end of superstitions and social ills, and generally accepted the imperatives of modern, Western civilization.

Gandhi, however, decided to be led by the people, guided by the lowest common denominator, and bow to their backwardness and poverty—and actually worship it. “There goes my people (sic). I must follow them, for I am their leader,” he said. So, he spewed outlandish ideas and radically rejected the Western civilization. Unsurprisingly, Gandhian ‘philosophy’ is a hodgepodge of ludicrous concepts which, if put in practice, would take us back to the Bronze Age, if not to the Paleolithic era.

Before we examine his ideas on various subjects, we should have a look at his attitude. In a way, Gandhi was the first Indian political leader who completely and comprehensively rebelled against the Western civilization. Yes, there were leaders before him—Tilak, Gokhale (Gandhi’s guru in politics), Lala Lajpat Rai, and others—but they all had imbibed the ideas of modernity and institutions of modern world, though often with a lot of reservations. The moot point is that despite all their reservations, they did not reject the Western civilization in toto; their fight was less against the Western ideas than against the people who brought them to India—the British rulers. In contradistinction to them, Gandhi was against anything British or Western. His opposition to the West was fundamental, albeit confused; he simply could not accept the West. So, Parliament was little better than a “prostitute” because it does not remain faithful to one party; and, when a reporter asked him what he thought of Western civilization, he famously replied, “I think it would be a good idea. [emphasis added]” As if the West was yet to be civilized! What Gandhi did not say, but did mean, was that India was civilized, despite many of its problems, and thus was superior to the West.

Compare this with Tagore’s view of the West. He wrote in Nationalism, “We must recognize that it is providential that the West has come to India… If Providence wants England to be the channel of that communication, of that deeper association, I am willing to accept it with all humility. I have great faith in human nature, and I think the West will find its true mission.”

Gandhi, on the hand, had little regard for the West. He did not just rave and rant against the British; his antipathy was quite evident, as we shall see. To be fair to Gandhi, he did not invent chauvinistic and anti-West pathologies; they existed before he appeared in the political arena. Swami Vivekananda had famously peddled the India-is-the-greatest-nation line. He was of the opinion that “we have yet something to teach to the world. This is the very reason, the raison d’etre, that this nation has lived on, in spite of hundreds of years of persecution, in spite of foreign rule and foreign oppression. This nation still lives; the raison d’etre it still holds to God, to the treasure-house of religion and spirituality.” The brown man’s burden!

Gandhi’s repudiation of West—the repudiation that made him click—was comprehensive. We begin with the sartorial aspects. If you look at any photograph of Congress leaders before his rise, you would see a group of gentlemen, attired as men of gentry should. After Gandhi, the group photographs have the leaders dressed simply, indistinguishable from the clothes common people wore. The leaders tried to identify themselves with the people.

Before Gandhi, the party was an outfit of grandees from different parts of the country, many of them the products of British rule, like the lawyers and landlords. They were surely not representative of the entire nation, yet they were the largest native representative group. For the British, in the beginning the party conventions were talking shops which had little influence on the people of the country and less on policy.

Over the years, after its birth in 1885, however, the Congress grew in relevance. By the time Gandhi appeared on the scene—that is, in the middle 1910s—the Congress had acquired some heft and gravitas and had undergone the moderate-extremist turbulence. Gandhi appeared not as one from the gentry, but as somebody who dressed, talked (he was not a great orator), and behaved like the man in the street. He successfully identified himself with the people—or, as intellectuals love to say, with the masses. And the people identified themselves with him.

The identification happened not just because of sartorial and behavioral patterns but also the peculiar, weird views Gandhi expressed. He embodied the anti-Enlightenment ideas, ideals, and postures. His views resonated with the most retrograde and benighted opinion of the country, the benightedness that was never suppressed by the thinking of Raja Rammohan Roy, Tagore, and others; Gandhi was benightedness personified.

Age of Enlightenment and benightedness

It would be instructive to briefly discuss here the Enlightenment. If there is any period in history which metamorphosed mankind, it is the eighteenth century, also called the Age of Enlightenment and the Age of Reason. To understand the Gandhian pathologies, we have to discuss the Enlightenment.

The Enlightenment was an intellectual movement that swept across Europe and North America. It was the crystallization of the Western intellectual tradition, incorporating ancient Greek, Latin, and Christian elements.

Human autonomy has been called “the means and end of Enlightenment.” The ‘light’ in the Enlightenment is invariably the light of reason, using which individuals can acquire knowledge, improve their lives, and declare their freedom from authority (ecclesiastical as well as political) to determine their own course of action.

In the essay, ‘What is Enlightenment’ (1784), Immanuel Kant wrote, “Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s understanding without guidance from another. This immaturity is self-imposed when its cause lies not in lack of understanding, but in lack of resolve and courage to use it without guidance from another. Sapere Aude! [dare to know] ‘Have courage to use your own understanding!’—that is the motto of Enlightenment.”

Kant sought to place reason on a pedestal. He wrote, “Nothing is required for this Enlightenment, however, except freedom; and the freedom in question is the least harmful of all, namely, the freedom to use reason publicly in all matters. But on all sides I hear: ‘Do not argue!’ The officer says, ‘Do not argue, drill!’ The taxman says, ‘Do not argue, pay!’ The pastor says, ‘Do not argue, believe!’… In this we have examples of pervasive restrictions on freedom. But which restriction hinders Enlightenment and which does not, but instead actually advances it? I reply: The public use of one’s reason must always be free, and it alone can bring about enlightenment among mankind.”

The tectonic movements in the Western intellectual tradition translated into fundamental changes—political, economic, social, religious, cultural, literary—not only in England and Scotland and Holland and France and Germany and America but also, indirectly, in the entire East and Africa. The story of the Age of Enlightenment transforming Western countries, strengthening their economic muscle, enhancing technological prowess, increasing military power, augmenting political might, and ultimately helping them embark on the imperialist project is too well-known to be repeated. From our point of view, two aspects of this globalization are pertinent. First, the Enlightenment also begot a few ideals which militated against the spirit of the eighteenth century. Second, the globalization that was accelerated by the developments of the eighteenth century was propelled, directly and indirectly, as much by the Enlightenment ideals as by the illegitimate progeny of the Enlightenment.

In the last two centuries, there have been a large number of philosophes, thinkers, and public intellectuals who have doggedly refused to accept the time-honored truths and the cogent arguments of classical liberal philosophers. Classical liberalism respects human existence and accepts the freedom of expression and action; one of its cardinal principles is that the unfettered individual is capable enough to take care of his own good. ‘It’s my life’, ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’—these are the mottoes. It is this attitude towards the individual that makes classical liberalism the true heir of the Enlightenment.

But this attitude was not accepted by all. The concept of negative liberty—the absence of state coercion, social control, etc., over the individual—was questioned, doubted, undermined, and ultimately discarded by major thinkers of positive liberty.

It was a long, arduous process; the austere philosophy of negative liberty was shown as barren and useless. It was austere because it did not—indeed could not—offer any utopia, that best-selling item in the market of enthusiastic philosophes and hot-blooded revolutionaries and nationalists. At best, it could offer the slave a mantra and a doctrine to free him from his chains; it cannot offer him the crown. But, as Albert Camus wrote, “The slave begins by demanding justice and ends by wanting to wear a crown.” The ideologues of positive liberty entice the slave; they sell him the meretricious charms of their utopias and fantasies.

Once sold, these utopias and fantasies undergo a metamorphosis; they invade the real world—usually with deplorable consequences. The denouement? As Camus wrote in The Rebel, “slave camps under the flag of freedom, massacres justified by philanthropy or by a taste for the superhuman…”

The fundamental problem with positive liberty is that invariably and inexorably it leads to some sort of collectivism—socialism, communism, nationalism, fascism, Nazism, or any other pathology. For an ideology oriented around a concept of positive liberty inescapably would need a group of people who are supposed to comprehend the reality, who are sagacious enough to understand the needs of the ‘real’ selves of the masses (The people in Leftist phraseology are usually referred as ‘masses,’ for they are presumed by the ‘knowing’ commissars to be such. They are ‘masses’ in need of direction, instruction, prescription, and proscription. In physics, mass is just a quantity, lacking direction). So, ‘the vanguard of the proletariat,’ Hitler’s coterie, and similar cliques always arrogate all powers to themselves. All in the name of a New World, New Society, New Man, or Master Race.

In the Indian context, positive liberty assumed the shape of nationalism. Like many others, Gandhi also portrayed the India of his dreams in Hind Swaraj, his seminal work. In the 1922 edition, he made his intentions very clear right in the beginning: “The booklet is a severe condemnation of ‘modern civilization.’ It was written in I908. My conviction is deeper today than ever. I feel that if India will discard ‘modern civilization,’ she can only gain by doing so.” Here, modern civilization was synonymous with Western civilization.

His tirade against the West begins with its political institutions: the British Parliament “is like a sterile woman and a prostitute. Both these are harsh terms, but exactly fit the case. That Parliament has not yet, of its own accord, done a single good thing. Hence I have compared it to a sterile woman. The natural condition of that Parliament is such that, without outside pressure, it can do nothing. It is like a prostitute because it is under the control of ministers who change from time to time. Today it is under Mr. Asquith tomorrow it may be under Mr. Balfour.”

Perhaps, Gandhi favored a Parliament that would have a ‘good character,’ like that of a faithful wife. It is another matter that, in the milieu of politics, such an arrangement is possible only under a dictator. Gandhi goes on discuss the demerits of Parliamentary system, how lawmakers ramble, how they had to toe the party line, how Carlyle lampooned Parliament a “talking shop,” and so on. His conclusion is unambiguous: “If India copies England [in introducing parliamentary democracy], it is my firm conviction that she will be ruined.”

There is nothing new in Gandhi’s condemnation of Parliament and, as an implication, of democracy. Many philosophers have talked about the shortcomings of democracy; problem is that there is no better alternative; the various replacements—Nazism, fascism, communism, etc.—have been tried. With calamitous consequences. Democracy may be bad, but it is the least bad system put to practice so far. These facts do not bother Gandhi; he goes on to recommend a system which is, to put it mildly, puerile.

Critique of Western civilization

Before that, however, he critiques civilization in general and Western civilization in particular. “Let us first consider what state of things is described by the word ‘civilization.’ Its true test lies in the fact that people living in it make bodily welfare the object of life. We will take some examples. The people of Europe today live in better-build houses than they did a hundred years ago. This is considered an emblem of civilization, and this is also a matter to promote bodily happiness. Formerly, they wore skins, and used spears as their weapons. Now, they wear long trousers, and, for embellishing their bodies, they wear a variety of clothing, and, instead of. spears, they carry with them revolvers containing five or more chambers. If people of a certain country, who have hitherto not been in the habit of wearing much clothing, boots, etc., adopt European clothing, they are supposed to have become civilized out of savagery. Formerly, in Europe, people ploughed their lands mainly by manual labor. Now, one man can plough a vast tract by means of steam engines and can thus amass great wealth. This is called a sign of civilization. Formerly, only a few men wrote valuable books. Now, anybody writes and prints anything he likes and poisons people’s minds. Formerly, men traveled in wagons. Now, they fly through the air in trains at the rate of four hundred and more miles per day. This is considered the height of civilization.”

What didn’t occur to Gandhi was the fact that the journey from the spear to the revolver, from the plough to the tractor, and from the bullock cart to the airplane is indeed progress; and it is surely a sign, if not the height, of civilization. The tractor and the revolver presuppose the existence of a certain level technological development; this development is the result of an advance in science; and science can grow only in a social, economic, cultural, and political milieu that is conducive for its existence. Technical excellence cannot be dismissed as something inconsequential, nor can it be dissociated from the social, cultural, and political moorings.

Gandhi had a very poor opinion about the spread of literacy and education, as evident from “Formerly, only a few men wrote…” Further, he seemed besotted with the abilities of Great Men who wrote “valuable books.” His admiration for these men was matched by his disdain for the riffraff who just poison the minds of other people. Typically, he does not elaborate on the criteria he had in mind to categorize what was valuable and what was poisonous.

The rambling continues: “It has been stated that, as men progress, they shall be able to travel in airship and reach any part, of the world in a few hours. Men will not need the use of their hands and feet. They will press a button, and they will have their clothing by their side. They will press another button, and they will have their newspaper. A third, and a motor-car will be in waiting for them. They will have a variety of delicately dished up food. Everything will be done by machinery. Formerly, when people wanted to fight with one another, they measured between them their bodily strength; now it is possible to take away thousands of lives by one man working behind a gun from a hill. This is civilization.”

Gandhi’s contempt for comforts and conveniences is striking; but even more conspicuous is his inability to comprehend that airplanes, cars, culinary delicacies, etc., are the consequences of multifarious developments over the centuries. He doesn’t have the intellectual acumen to understand that the comforts and conveniences he dislikes so much are great feats of mankind.

So, the tirade against the march of mankind goes on: “Formerly, men worked in the open air only as much as they liked. Now thousands of workmen meet together and for the sake of maintenance work in factories or mines. Their condition is worse than that of beasts. They are obliged to work, at the risk of their lives, at most dangerous occupations, for the sake of millionaires. Formerly, men were made slaves under physical compulsion. Now they are enslaved by temptation of money and of the luxuries that money can buy.”

Blend of romanticism and ignorance

This is a blend of Rousseauian romanticism and ignorance of history. The time in which Gandhi wrote Hind Swaraj (1909) was perhaps the worst phase of industrialization from the perspective of workers. To that extent, his criticism is justified. But to compare factory workers with the slaves of yore is a gross and misleading exaggeration, for there is a world of difference between being chained and living miserable life because of lower wages; the former is imposed, while the latter is voluntary.

Gandhi also saw evil in the beneficent aspects of modernization: “There are now diseases of which people never dreamt before, and an army of doctors is engaged in finding out their cures, and so hospitals have increased.” It is an indisputable fact that when he wrote the book, life expectancy was much higher in India and in the West than it was in the middle of the 18th century when the Industrial Revolution began. It was made possible by armies of doctors and spread of hospitals.

This is a typical feature of Gandhi’s writing: sweeping generalizations are made, offering little empirical evidence and less logic. So, he keeps flitting from once subject to the other. On ethics and faith, he writes: “This civilization takes note neither of morality nor of religion… Civilization seeks to increase bodily comforts, and it fails miserably even in doing so. This civilization is irreligion, and it has taken such a hold on the people in Europe that those who are in it appear to be half mad. They lack real physical strength or courage. They keep up their energy by intoxication. They can hardly be happy in solitude. Women, who should be the queens of households, wander in the streets or they slave away in factories. For the sake of a pittance, half a million women in England alone are laboring under trying circumstances in factories or similar institutions. This awful act is one of the causes of the daily growing suffragette movement.”

This is a hodgepodge of false statements, misconceptions, and retrograde views. Europeans lacking physical strength and courage? Was Gandhi totally cut off from the reality? How could he or anybody else say such things about the folks who conquered large swathes of the world and ruled over diverse populations? Europeans, originally inhabitants of a small continent, held sway on all continents when Gandhi wrote his book, and he accuses them of being weaklings!

He also reveals his medieval, patriarchal mindset. The best thing a woman could do, in his scheme of things, was to be a housewife.

Unsurprisingly, the chapter ends calling civilization a “disease.”

Contrast this with what Will Durant, one of the greatest historians and authors, wrote about the subject: “Civilization is social order promoting cultural creation. Four elements constitute it: economic provision, political organization, moral traditions and the pursuit of knowledge and the arts. It begins where chaos and insecurity end. For when fear is overcome, curiosity and constructiveness are free, and man passes by natural impulse towards the understanding and embellishment of life.” Further, “man differs from the beast only by education, which may be defined as the technique of transmitting civilization.”

Gandhi’s cerebral horizons were not wide enough to grasp the immensity and complexity of civilization in general and of Western civilization in particular. For he was, and remained all his life, a rustic philistine with little use of culture, creativity, or cultural creation. Like the bumpkin in a metropolitan city who is only flustered and frustrated by inconveniences all around—the traffic, the noise, the pollution, bustle, crowds, anonymity, impersonality, et al—and has nothing to do with the refinements it offers, Gandhi too could notice only the underbelly of the West at that point of time.

In a perverse way, he was the true Indian, almost completely unaffected by (what Hindu nationalists call) Macaulayan influences. He was unable to comprehend the West, its rise, and its influence on the rest of the world. So, his rendezvous with the West remained quite uneventful in the sense that it failed to evoke a profound response as it should have. V.S. Naipaul, in India: A Wounded Civilization, has discussed the subject, but he got lost in the obfuscations and jargon of psychology, whereas the treatment needed was philosophical and ontological.

What I mean by true Indian is the person whose world comprises his family, household, and community; all his concerns are confined to this microcosm; beyond that lie the ultimate reality, the Brahman. His macrocosm is the sum total of his microcosm and the ultimate reality. He doesn’t have much idea about public and political life—that is, mundane existence in the company of individuals who are not part of the community. Everything is ordered in accordance with the cosmic law, karma, about which various Hindu schools of philosophy say various things and about whose inexorability there is some comprehension among the people. The Hindu way of life, at least in the second millennium, was the nonstop journey from the personal to the spiritual, bypassing the stage of the political, the scientific, the rational, and the philosophical.

This is the reason that no Indian ever traveled to any place in the world, came back, and wrote about it. It is well known that travelers from all over the world—China, Europe, the Arabian world—have visited India and written about the social, economic, cultural, religious, and political conditions of the country. In fact, much of what we know about our own history is because of their writings. But there was no reciprocation from our side. Trade with other countries is as old as our history, so it cannot be said that our ancestors were not aware of other lands. We have a long coastline, some seafaring tradition; there were Indian traders and seafarers. But there were no Indian monks, traders, travelers, and adventurers writing about other countries and peoples. This was primarily because of the shackles which Brahmins had placed on our minds.

British rule broke those shackles. Gandhi was unnerved by this freedom. His life was devoted to devising new chains to enslave us—various forms of medievalism and collectivism, a perverse nationalism, and a million illiberal proclivities.