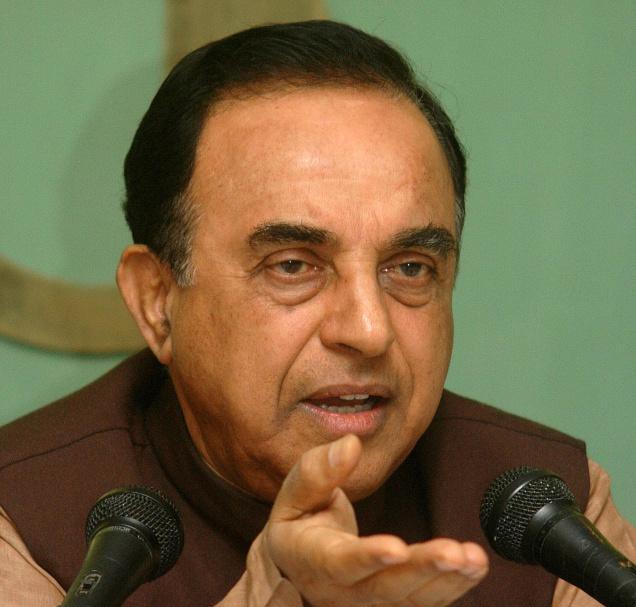

The issuance of a non-bailable warrant against BJP leader Subramanian Swamy by an Assam court is an assault on the freedom of expression that is enshrined in our Constitution. He has been accused of making a hate speech. Specifically, the form of assault is a strategic lawsuit against public participation (SLAPP) which intends to bully, suppress, and censor dissent.

The SLAPP idea is simple but low-cost and effective: file a criminal case against your adversary or even the person whose views you don’t like; given the fright that court-kachheri ke chakkar causes in general, the target is likely to panic and succumb. And if the accused lives in a distant location, as Swamy does, the rigors of travel and stay in a strange city are added to the travails of legal proceedings—dealing with lawyers, waiting for hearings, the fear of being thrown behind bars, the expenses, the impact on livelihood and professional life, the social fallout, et al.

In his petition against the order of the Karimganj trial court, Swamy has approached the Supreme Court. The alleged hate speech was made on March 15 at Kaziranga University. According to Swamy, “Karimganj has a majority Bengali-speaking population, with close ties to Sylhet in Bangladesh. It is isolated from the rest of Assam and is dominated by illegal Bangladeshi migrants who are hostile to Assamese speaking majority of the rest of Assam; and the Petitioner has apprehensions for his safety when he appears in Court there.”

Quite apart from the threat to his life in responding to the court summons, there is the issue of curtailment of right to freedom of expression. In the “past few years,” Swamy said, several sections of the Indian Penal Code have been invoked against him, “sometimes mala fide and maliciously, by various authorities to penalize him for his clearheaded extensive research and his ideological beliefs and thereby make him conform to the norms of certain special ideological and religious groups.”

That is the moot point: in the name of stopping “disharmony or feelings of enmity, hatred or ill-will” between religious groups and checking the “outraging” of religious feelings, the Congress after Independence and even before 1947 has tried to silence all viewpoints other than its own, especially those pertaining to Islam and secularism. Any criticism of Islam, howsoever scholarly the tone and howsoever noble the intent, is equated with communalism. Whether it is an academic, journalist, or politician, anybody not conforming to the official ideology of the Congress is socially ostracized and legally penalized. Swamy is one of the many people who have been persecuted.

It would be instructive to scrutinize the penal sections that criminalize offence to feelings. Few, if any, have ever asked in India: Can offending the feelings or hurting the sentiments of somebody be a ground for legal action? Let’s look at the real issue—the validity of demands for legal actions because feelings were offended—from a legalistic point of view.

The Indian Constitution imposes “reasonable restrictions” on the Fundamental Right to freedom of expression. Reasonable restrictions appended to the Right to Freedom of Speech and Expression in Article 19 (a) pertain to “the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence.”

Even as these restrictions are an affront to individual liberty and genuine democracy, these are themselves purported to be “reasonable.” In other words, these can be imposed only if there are reasonable grounds for harming national security, jeopardizing friendly relations with foreign countries, disturbing public order, offending decency or morality, contemning court, leading to defamation, or occasioning incitement to an offence. Nowhere is it mentioned that offending the feelings or hurting the sentiments of somebody can be a ground for curtailment of the freedom of expression.

The grounds restricting the freedom of expression have to be reasonable, and not sentimental, not only because it is the Constitutional position but also because reasons can be objectively debated; sentiments can’t be. Merriam Webster describes ‘feeling’ as, among other things, ‘an emotional state or reaction’ and ‘often unreasoned opinion or belief.’ Similarly, the dictionary defines ‘sentiment’ as ‘an attitude, thought, or judgment prompted by feeling’, ‘predilection’, ‘a specific view or notion’, ‘opinion’, ‘an idea colored by emotion’, etc. It is, therefore, crystal clear that the defining feature of feelings and sentiments is subjectivity.

The imperatives of law and public administration, on the other hand, are molded by objective realities. Poetry is to sentiments and subjectivity what political philosophy is to statecraft, jurisprudence, and objectivity. So, Plato said in Republic that there is an old quarrel between philosophy and poetry. According to him, if poetry is allowed in his ideal state, “not law and the reason of mankind, which by common consent have ever been deemed best, but pleasure and pain will be the rulers in our state.” This was the reason that he banished poets from his ideal state.

In India, however, the foundational principles of polity are poetic in nature. This is the reason that our penal code still has sections which militate against the spirit of the Constitution. Two of them have been invoked against Swamy: Section 153A and Section 295(A). Section 153A says that “Whoever (a) by words, either spoken or written, or by signs or by visible representations or otherwise, promotes or attempts to promote, on grounds of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, caste or community or any other ground whatsoever, disharmony or feelings of enmity, hatred or ill-will between different religious, racial, language or regional groups or castes or communities… shall be punished…” (emphasis added). Similarly, Section 295(A) says, “Whoever, with deliberate and malicious intention of outraging the religious feelings of any class… shall be punished…” (emphasis added).

Unfortunately, our political class not only has not only persisted with such illiberal provisions but also time and again introduced even more draconian ones to tame the citizenry; the latest example was Section 66A which was, thankfully, invalidated by the Supreme Court.

It is time somebody fought to get the retrograde Section 153A and Section 295(A) dumped. Would that somebody be Subramanian Swamy?