Budget-making today is a tough call for a Finance Minister trying to reverse the past decline caused by the UPA’s policies. The Indian economy, for example, decelerated from an 8.4 per cent growth rate in GDP in 2003-04 to 4.8 per cent in 2013-14. The UPA’s decade of economic decline has been wrongly attributed to the global economic meltdown especially during the last six years of the decade.

Therefore, recovery and growth need a different policy today, and require choosing a new framework of objectives, priorities, strategy and resource mobilization measures in constituting a Budget.

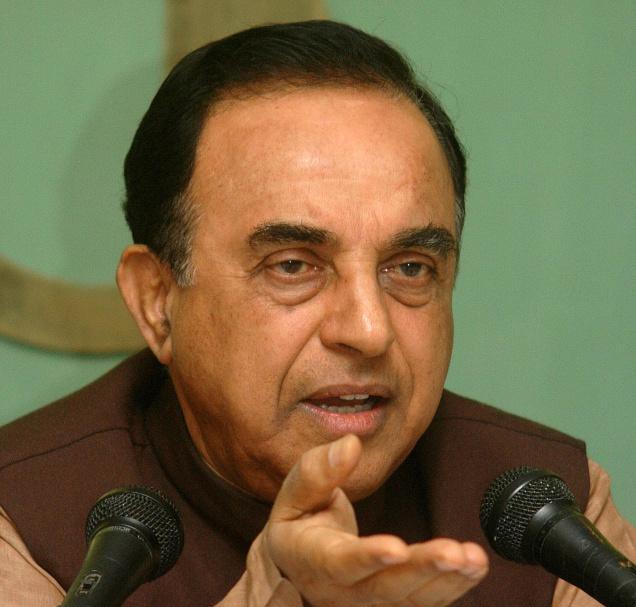

Budget 2015-16 is a serious attempt to usher in such a new framework. An analysis of how far Finance Minister Arun Jaitley has succeeded and what more remains to be done for a successful turnaround is the concern here in this article.

The Indian economy has declined because of the peculiar Indian “invention” of that perfidious financial derivative called Participatory Notes or PNs, otherwise known as the crony/crooked facilitator for black money-based portfolio investment. No other country would think of such a derivative.

The Budget does not treat PNs as a time bomb and to seek to abolish this derivative, as the Tarapore Committee had wanted. Actually, PNs have been even more legitimized by enhancing their status to that of FDI inflow.

“The Indian economy has declined because of the peculiar Indian ‘invention’ of a perfidious financial derivative called Participatory Notes.”

The Finance Minister ought to have abolished PNs in this Budget to stabilize the economy. I do not know if Jaitley was even shown this legitimization of PNs which is in the fine print of the Budget documents.

He has introduced many new measures, such as a vastly increased agricultural credit facility, the new Mudra Bank to fund the underfunded, especially Scheduled Caste/Tribe entrepreneurs, tax-free bonds for infrastructure development, ultra-large power plants of 4,000 MW, monetization of hoarded gold by paying interest on gold deposit accounts in banks and ease of doing business in India by a digitization of procedures. But this is not enough to kick-start the economy since Jaitley has not embedded such piecemeal measures in the larger picture of economic reform and budgetary restructure.

Today, for example, there is a budgetary crisis looming on the horizon because the allocations for major heads of expenditure—government employees’ salaries, pensions, police, defence, subsidies, interests to be paid for past loans taken by the government, etc., and which now cover 98 per cent of the current and capital account revenues accruing to government—cannot be reduced without creating a political crisis.

These allocations are revenue expenditures, and hence not asset-building or investments for development projects.

Moreover, in the past, in the revenue budget, these expenditures far exceed the revenue. Thus, the revenue budget has been in huge deficit, and which is covered by taking more loans from public sector banks and creating a surplus in the capital account by trimming investment allocation.

In the Budget, we find this is continued because Non-Plan Expenditure has risen 11 per cent while Plan Expenditure has been stagnant. In a financially healthy economy, it should be the other way around—surplus on the revenue account, i.e., revenue exceeding expenditure, and a deficit in the capital account, i.e., investment exceeding amortization.

This situation, however, cannot continue for long because loans from public sector banks to the government to pay for the overall deficit in the Budget have to be paid back. It will require a major recapitalization of banks to meet the Basel III norms or else the public sector banks may go bankrupt by 2017. A time bomb is ticking here.

The big picture we have to usher in is an Indian economy growing annually at 10 to 12 per cent by inducing the current household saving rate of 29 per cent of income to rise again to the rate of 36 per cent.

To become a developed country in the foreseeable future, India’s GDP will have to grow at 10 to 12 per cent per year for at least a decade. A 12 per cent GDP growth rate per year will mean a doubling of GDP every six years, and that of per capita income, doubling every seven years. That should be a stated goal of every budget and not just a “balancing the books” exercise.

Technically, this is within India’s reach, since it would require the rate of investment to rise while productivity growth will have to ensure that the incremental output-capital ratio declines from the present 4.0 to 3.0. Productivity increases can be achieved by cutting transaction cost in the ease to do business and by motivating labor with incentives to work harder.

Further, if we reduce transaction cost by eliminating corruption, then the current incremental capital-output ratio will easily fall from 4.0 to 3.0.

This can also be sustained by directly, and not indirectly, enthusing the middle class—which today can be achieved only by abolishing personal income tax. In this Budget, the middle class has little to cheer about. The morning-after announcement of petrol and diesel price hikes—even while internationally crude oil price continues to be in decline—has only further discouraged the middle class. India’s middle class urgently needs some good news.

India has many advantages to achieve a booming economy such as a demographic dividend, agriculture that has internationally the lowest yield in land and livestock-based products, and also, by WTO reckoning, the lowest cost of production, 12 months a year of farm-friendly weather, a highly competitive, skilled and semi-skilled labor force and low wage rates at the national level, the advantages of which have already been proved to the world by the outsourcing phenomenon. We have a young population—the average is 28 years when compared to the US’s 38 years, and Japan’s 49 years—that is the base for it to usher in innovation in our production process.

Since the worldview of economic development has now completely changed, economic development is no more thought of as being capital-driven but knowledge-driven. For application of knowledge, we need innovations, which means more original research, and more fresh, young minds out of the cream of youth to be inculcated with learning and to be at the frontier of research.

The unintended consequences of past policies should not make us squander this “natural resource” of youth we have acquired. Today, using proper policy application for the young, we must realize and harvest this demographic potential.

Thus, these goals have to be at the core of the economic agenda underlying the making of Budgets. But for all that to happen, more vigorous, market-centric, economic reforms are necessary and need to be at the centre-stage of the nation’s attention in a Budget and not be overwhelmed by what corporate-driven, media hype expects of a Budget.

Looking ahead positively, the nation still has four more annual Budgets to see, and which will hopefully set the stage for India’s economic renaissance in the next decade.