Budget 2015-16: Bad politics

Ravi Shanker Kapoor | February 28, 2015 1:20 pm

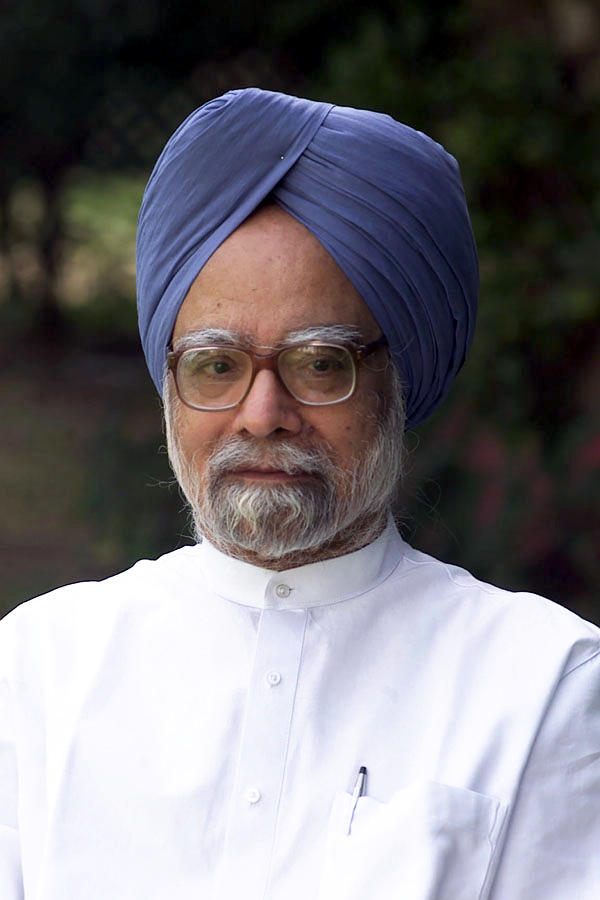

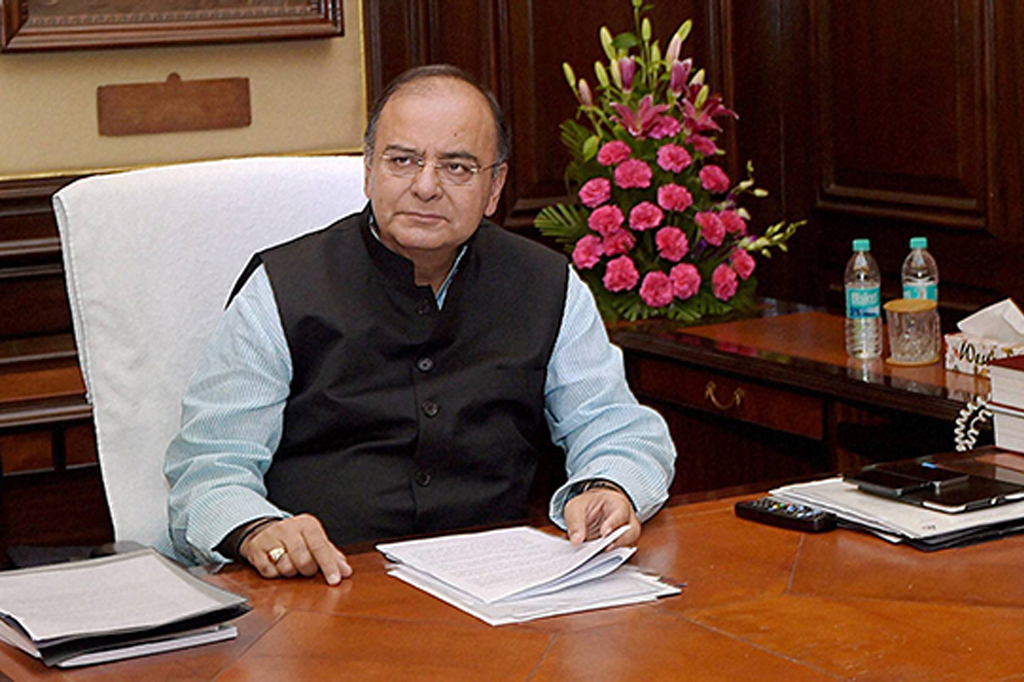

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley’s second Budget has been widely hailed, especially by industry, as landmark, super-Budget, etc. This is not surprising, given the fact that it is much bolder than the one he presented in July last year; that was almost an extension of the UPA’s. Budget 2015-16, on the other hand, is quite different in approach than the previous one; now emphasis is on fiscal consolidation as well as robust growth and development. However, its drawbacks, which relate to politics and public discourse, can scarcely be ignored.

Unfortunately, few have discussed the political fallout. Jaitley has brought down the corporate tax rate from 30 per cent to 25 per cent, even as he has refused to increase the nil-tax slab for individual income-tax payers (read middle classes). A consummate lawyer as he is, he made an excellent case for providing relief to business: “The basic rate of corporate tax in India at 30 per cent is higher than the rates prevalent in the other major Asian economies, making our domestic industry uncompetitive. Moreover, the effective collection of corporate tax is about 23 per cent. We lose out on both counts, i.e. we are considered as having a high corporate tax regime but we do not get that tax due to excessive exemptions.”

As a consequence, he continued in his Budget speech, “a regime of exemptions has led to pressure groups, litigation, and loss of revenue. It also gives room for avoidable discretion. I, therefore, propose to reduce the rate of corporate tax from 30 per cent to 25 per cent over the next four years. This will lead to higher level of investment, higher growth, and more jobs. This process of reduction has to be necessarily accompanied by rationalization and removal of various kinds of tax exemptions and incentives for corporate taxpayers, which incidentally account for a large number of tax disputes.”

Impeccable logic indeed, but such impeccability was missing when it came to income-tax payers—who, by the way, happen to be the Bharatiya Janata Party’s main constituency. In India, anybody earning Rs 2.5 lakh or more a year has to pay income tax. This is one of the lowest minimum slab rates in the world; the need of the hour was the doubling of the slab. But, instead of that, the Finance Minister has satisfied himself by just offering some tax benefits by way of savings.

This is not just bad economics but also bad politics, for the government has made itself vulnerable to the charge—already hurled at it by opponents—that it is pro-industry and against the common man. Now, such allegations will have a ring of credibility around them. Apparently, Jaitley, who has the reputation of being a drawing room politician, is unaware of this feeling in the Middle India.

If and when such feeling intensifies, as it is likely to in due course, Jaitley’s “roadmap for accelerating growth, enhancing investment and passing on the benefit of the growth process to the common man, woman, youth, and child” may become difficult to follow. There is a possibility that the demands to adopt anti-reforms policies would mount—from within as well as without. It is no secret that there are several elements in the Sangh Parivar which are against reforms; they may gain strength if the climate of opinion turns against the government and it is seen as the handmaiden of big business.

If that happens, it will call for a great deal of courage on the part of the government to stick to the road of liberalization. At present, there is a deficit of nerve as well. To be fair to Jaitley, unlike in his previous Budget where he did not dare to even utter the word ‘disinvestment,’ he has talked about “strategic disinvestment”—which is a polite expression for privatization. But, typically, he was cagey regarding spelling out the details. Evidently, he lacks the courage of conviction regarding privatization.

In a nutshell, the good intentions and sound provisions of Budget 2015-16—which are numerous—may not be concretized because of inadequate political acumen and the lack of requisite boldness.