The five-day coal strike, which caused a loss of Rs 70 crore the very first day, epitomizes several ills of the country’s political economy. The most important of them is the issue of representativeness of the trade unions of the five lakh coal workers. The fact that the RSS-affiliated Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS) is also among the five unions underlines the confusion within the Sangh Parivar over the contours of the policy framework.

Let’s begin with the claim of the union leaders that they represent the striking workers. It is fair to assume that they work for the welfare of workers. But what is their position? They say that they are opposed to “disinvestment [in] and restructuring of state-run Coal India” and the “process of denationalizing of coal sector.” Fact, however, is that whether or not a state-run company or a sector should be privatized is a decision that government should make. In the event of any such decision if workers are affected adversely, trade unions would be in their right to safeguard the interests of employees. Otherwise, their stance would be regarded as political.

Evidently, trade unions take political positions because the biggest ones are linked to major political parties. The case of BMS is curious, though; it is part of the Sangh Parivar, whose economic philosophy tends to lean more towards socialism rather than to the pro-reforms agenda of the Narendra Modi government.

Further, the BMS, not unlike the Trinmool Congress, is often keen to out-Left the Left, thus coming up suggestions similar to the ones made by communist parties. For instance, a resolution at the 16th National Conference of BMS held at Jalgaon, Maharashtra, in July 2012 urged the government to “stop forthwith the economic and labor reforms based on Liberalization, privatization and globalization,” ban forward trading, “stop forthwith and withdraw all measures taken on financial de-regulation, banking reforms and opening up of banking and insurance sectors to foreign capital,” and “universalize social security and welfare spending…” Could the CPM have demanded anything different?

Quite apart from the quandary of combating a fraternal outfit, there was the problem of gradualism. The Modi regime, at present at least, wants to adopt measures that are least controversial; the real, tougher issues it wants to postpone for sometime in the future. It is prudent to avoid controversies, but there comes a time when becoming too politic can be politically damaging in the long run. This was that time. The government, however, chose the easy path of non-confrontation, which was almost like surrender to the pressure tactics of ideologically motivated union leaders.

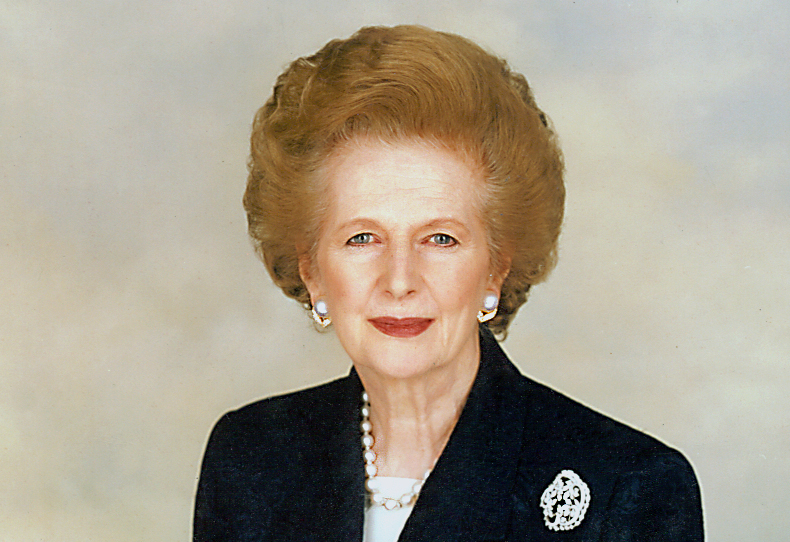

Three decades ago, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher faced a similar situation—the miners’ strike. The BBC termed it as “the most bitter industrial dispute in British history.” And this was the strike that helped the UK get rid of the distortions in the coal sector, check the bleeding of the public exchequer, and revitalize industry. In sheer political terms, Margaret Thatcher and the Conservative Party emerged as victorious. The political clout of British trade unions was greatly reduced.

This was the time for Modi to show his mettle, boost economic liberalization, and gain further political mileage. For linked with coal are sectors like power, all of which are crying for reforms. A firm resolve on the part of the government would have gone a long way ushering in economic development, improving the business environment, and lifting investor confidence. As Brutus said in a speech in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, “There is a tide in the affairs of men, which taken at the flood leads on to fortune.”

But the government agreed to major demands of the unions. “There is no intention for denationalization of CIL. The present and future interest of CIL employees will not be affected in any manner. CIL will be protected and there need be no apprehension about its ownership or management going into private hands,” Coal & Power Minister Piyush Goyal told reporters after a marathon meeting, lasting more than six hours, with the trade union leaders.

In other words, no big-bang reforms, just a whimper.